The recent invitation to respond to the statement “Don’t Teach the Test” was under discussion in the New York Times: Invitation to a Dialogue series. The question was posed by Peter Schmidt, the director of studies at Gill St. Bernard’s School, and he singled out two tests in particular: the SAT and the Advanced Placement Tests.

The recent invitation to respond to the statement “Don’t Teach the Test” was under discussion in the New York Times: Invitation to a Dialogue series. The question was posed by Peter Schmidt, the director of studies at Gill St. Bernard’s School, and he singled out two tests in particular: the SAT and the Advanced Placement Tests.

Schmidt suggested that the SAT should be eliminated as a requirement for college on the basis of economic inequality. Students who have the finances to take prep courses or hire tutors have an advantage, and Schmidt suggests that, “our colleges are further promoting the inequities of our society.”

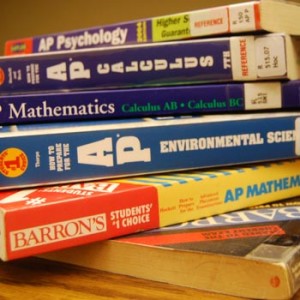

Schmidt also called for the end to Advanced Placement (A.P.) courses in high school, saying that they

“too often fail to prepare students adequately for college-level course work. They also put pressure on students to perform well on the A.P. exams in the spring, leaving them exhausted and lacking a spirit of intellectual curiosity.”

Full disclosure: I teach Advanced Placement English Literature, and I have served as an A.P. Reader.

That said, I believe Schmidt is right about the pressure the testing for these courses places on students. I agree that these students are exhausted the first two weeks of May since students who take A.P. courses often take more than one A.P. class. Many students are scheduled for two separate tests on the same day. But as to his assessment that the A.P. courses do not prepare students for college level work, I must respectfully disagree.

That said, I believe Schmidt is right about the pressure the testing for these courses places on students. I agree that these students are exhausted the first two weeks of May since students who take A.P. courses often take more than one A.P. class. Many students are scheduled for two separate tests on the same day. But as to his assessment that the A.P. courses do not prepare students for college level work, I must respectfully disagree.

Students who take A.P. courses recognize that they may or may not receive college credit for the course. College credit is given based on a student’s test score (minimum a level “3” on the A.P. English Language or Literature) and the willingness of the college to accept that score in lieu of an undergraduate course. As a result, there are no guarantees of college credit in an A.P. class; however, colleges do look to see if students are taking A.P. classes as an indication of their academic ambitions.

The A.P. exams in all subject areas are a mix of multiple choice questions and essay responses questions. In the A.P. English Literature exam, there are 55 challenging questions on five or six literature selections. Students need a command of vocabulary and the ability to “close read”, a skill that was the hallmark of A.P. courses long before the Common Core State Standards. But the most demanding part of the AP English Literature exam is the essay section where students write three essays in response to three prompts in two hours.

My students practice writing to these prompts throughout the school year. They learn to read, annotate, and draft quickly, but Schmidt raises a good question.

Does the A.P. test prepare students for college?

In responding to Schmidt’s concern, I have thought about how my student’s responses to the essay test questions are not the only measure for determining student understanding. A good A.P. course incorporates the practice of revising drafts written for a practice test. There is always a gem of an idea in these hasty constructions. There is always some hypothesis that student will discover as he or she “writes into” the prompt, something I have previously referred to as a “manifesto in the muck.” A good A.P. course provides a student with the chance to take that essay draft, and expand and revise. A good A.P. course gives students the chance to start again with the end of the draft in order to begin a better essay.

Schmidt complains about “the lack of imagination and creativity” that “are the cornerstones of genuine learning,”but these generalizations are not true. I know first-hand that there is nothing to stop a student’s imagination or creativity in responding to a work of literature in an A.P. course. Some of the most amazing statements or ideas I have read have come from students undergoing the intellectual crucible of writing an organized essay in under 40 minutes. In reading these practice drafts, some ripe with grammatical errors and misspellings, I will pause with my red pen suspended, repeating to myself, “First do no harm”, as I leave a draft untouched. A.P. advises instructors to “reward the student for what they do well”, even on a practice test.

There are too many reasons to not like the standardized tests that are choking education today; the limited data that standardized testing yields is often not worth the time and expense. Frankly, I am no fan of the College Board. The limitations of the A.P. test, however, does not mean that an A.P. course is not valuable.

The A.P. test, like all standardized tests, is a single metric measure, but an A.P. course is a much broader experience. So, yes, I teach to the test, but I also teach the A.P. course as a preparation for the rigors of college level work, and in particular, I teach the course so that my students will have the option to waive a 100 level composition class giving them the option to take a course in their major field of study.

Schmidt concluded his invitation with an impassioned plea,

As E. M. Forster wrote more than a century ago in Howards End, in addressing the shortcomings of British universities: “Oh yes, you have learned men who collect … facts, and facts, and empires of facts. But which of them will rekindle the light within?”

I would argue that my A.P. class is the only place in my curriculum where I can offer the writings of E.M Forster, if for no other reason than to see how students would respond to that literary prompt. I know that in their responses, there could be one from a student who, writing under intense pressure, could draft a sentence or two that would reveal a “kindle of light within.” Whether that student response would be in a test booklet written during the A.P. test or not does not matter.