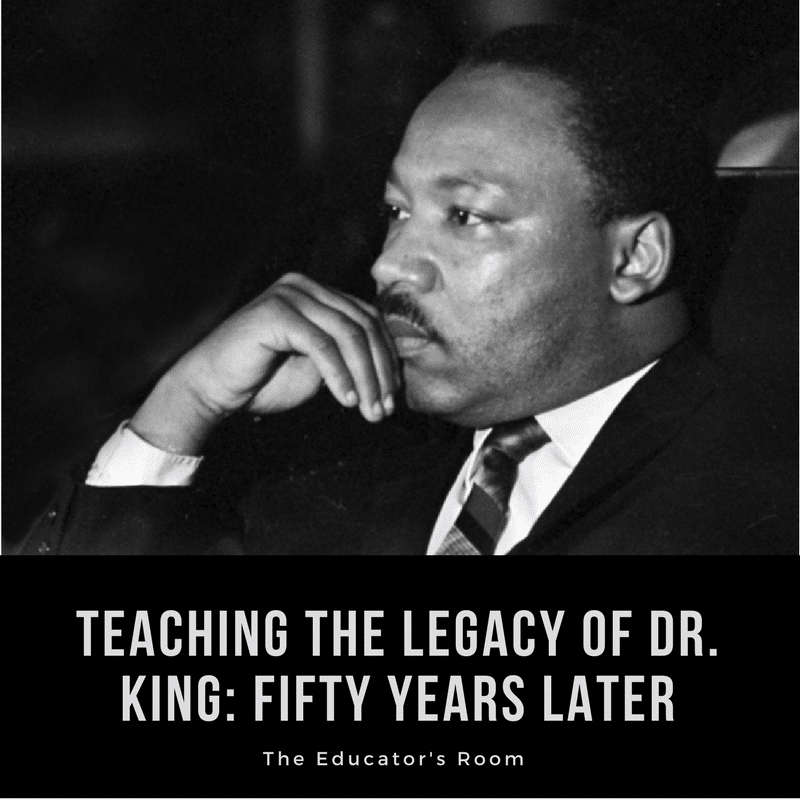

I sit to write on the waning hours of April 4, 2018, fifty years after the assassination and death of Martin Luther King, Jr. I was seven when we all heard the news of his death. Even at that young age, I knew something had happened that would change the direction of my nation, indeed; my world. Two months later, we would hear about Robert K. Kennedy’s death, an event that would propel me backward five years to the death of a beloved president, and this young boy in Baltimore County would begin to try to understand the history of the nation unfolding around him. My own destiny, like millions of others, was tied up in the destiny of this African-American preacher from Atlanta.

Dr. King echoed the very emotion I was experiencing in his most famous speech:

For many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

What Does King’s Death Mean to America today?

The death of Dr. King is an event that forces us as Americans to ask about his life and what it means to us as a nation. Martin Luther King, Jr was a man of peace, originally a Baptist minister, someone who preached the gospel of God’s love for all people, the importance of nonviolent direct action in the tradition of Gandhi, demanding justice in its many forms for all American citizens and even for all humanity across the globe. But he died a violent death at end of the muzzle of a gun, and it is this contradiction that elevates him to the status of a martyr in the pantheon of American history, along with Abraham Lincoln, JFK, and RFK. Even though King never held elective office, we revere him as a great American leader, we have set aside a federal holiday celebrating his birth, a day that has become synonymous with a time of national service. His “I Have a Dream” speech is well known around the world, and it is these words that now act as the standard for social relationships that call for the end to prejudice of all kinds:

[bctt tweet=”I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. ” username=””]

Indeed, our nation continues to move towards this ideal spoken in August of 1963, not yet fully realized because we still have scenarios of white supremacists marching in Charlottesville and the seemingly indiscriminate killing of unarmed black men by white police officers. His words now apply not only to fighting prejudice based on skin color but as King had hoped through his 1968 “Poor People’s March,” he also wanted his words to address economic standing, as well as national origin. In today’s social context, our society is in the early stages of applying his call to justice to sexual orientation as our nation struggles to accept diversity in all of its many forms.

What He Achieved In Life and In Death

His life and actions have become a critical part of the national history and government curriculum, and in a deeper sense, his life and teachings, have become the conscience of the nation, constantly calling upon all of us to reflect on whether our American ideals of justice, equality, and fairness. These lofty ideas are being realized in our national discourse and in social policy. His mission started as a way to end racial segregation in America, but with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he was able to witness the death of Jim Crow and the Segregated South. He also spoke out against white complacency — what he called “the white moderate” in his Letter From a Birmingham Jail:

I must make two honest confessions to you, my Christian and Jewish brothers. First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

[bctt tweet=”I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Council or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice.” username=””]

Dr. King is a singular figure in human history, standing for the highest ideals that humans can represent. His contribution to our moral evolution goes far beyond the political — it extends into the spiritual because he embodied the morality that he found in the teachings of Jesus Christ. He would not allow hatred and prejudice to be the norm in a nation that was founded on the principle that “all men were created equal.” Moreover, he fought the sin of racism with non-violence, holding that fighting back against violence only lowered the victim to the level of his oppressor.

But he also was subject to criticism on both the right and the left. He suffered death threats from White Supremacists and Klansmen but was also criticized as being a gradualist and pacifist by the militant wing of the civil rights movement. His outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War brought him under suspicion by the federal government and was placed under surveillance by the FBI. His activism fought the breadth of America’s political and social hypocrisy during the 1950s and the 1960s because his mission was broader than those goals — his mission was overarchingly spiritual.

It is still a question of a debate: would the nation have accelerated its march towards civil rights had Dr. King had lived? Or was it the very fact that he was martyred that brought about rapid social change that characterized the 1970s and 1980s in the wake of his assassination? We will never really know, but we can consider the possibilities.

Teaching King’s Legacy: Keeping it Real

It is easy to elevate Dr. King to the status of American hero so that we are able to say the problems of racism, classism, and sexism have been cured in this country. For many Americans, it seemed as though King’s dream had come one step closer to reality when the first African-American president took office on January 20, 2009. But in the post-Obama era, it appears that much of the overt racism inherent in American society had been uncovered again, and in many ways, it has come out of hiding. The economic and political gains of the civil rights movement are threatened through systemic and institutionalized racism, bias in education and in the criminal justice system that has resulted in the mass incarceration of African-American men and a lack of economic opportunity in many cities and rural areas of the nation.

King would not remain silent about these and other modern-day issues. The epidemic of gun violence in America, the use of American military force to impose American foreign policy around the world, the concentration of wealth and its inequitable distribution among the 1% of Americans, the existential threat of climate change and challenge of correcting it, the plight of immigrant children who now call themselves “Dreamers,” and the Islamophobia that increased in the wake of September 11 are all issues that Dr. King would have taken on and used his eloquent oratory to fight and to raise the conscience of Americans, just as he did when he fought against de jure and de facto segregation in both the South and the Northern cities of this nation.

“If you want to be great, you gotta serve.”

Aside from actively teaching the entire “I Have A Dream” speech, the record of Dr. King’s speeches contains one other message I like to share with my students, especially on his birthday. King expressed this sentiment much in the Christian tradition of the words of Jesus who said “The first shall be last, and the last shall be first” (Matthew 20:16). In a sermon delivered on February 4, 1968, at Ebenezer Baptist Church entitled “The Drum Major Instinct”, Dr. King reminded his audience:

And so Jesus gave us a new norm of greatness. If you want to be important—wonderful. If you want to be recognized—wonderful. If you want to be great—wonderful. But recognize that he who is greatest among you shall be your servant. (Amen) That’s a new definition of greatness.

Like Jesus, Dr. King reorganized our national priorities for us and led the way doing it. To be a great nation, we must work to raise up those who have experienced discrimination, hatred, and persecution. He demanded of us that America must “live out the true meaning of its creed” by serving one another and by serving the community of nations. He knew that we were a nation blessed by Providence with vast natural and human resources, but that those resources must be distributed in a fair and equitable way for America to live up to its Christian ideals. So as we remember his death, both in and out of the classroom, let us celebrate the way he lived his life, in service to others. That might be the one thing among many that made him great.

Well written!