[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

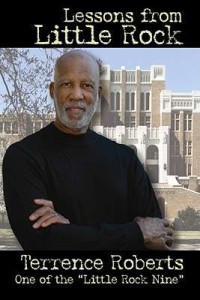

Last November, I had the privilege to attend a conference of educators like myself, who work primarily with dropout recovery and dropout prevention programs. These are the students society labels “at risk,” but whom these teachers call “at-promise” students. The keynote speaker was Dr. Terrence Roberts. He is one of the Little Rock Nine, and he spoke to the gathering of over 130 alternative school educators about his experiences during that first year he went to Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. He also spoke about how his experiences later in life with racism connect to how dropout recovery educators can relate to their students. The same ideas apply to all educators (after all, we are all in the business of dropout prevention).

It was a striking experience to be in the same room as someone who has personally made history – especially because he made that history when he was only a teenager. His words reminded me that his experience, while incredibly unique, is also universal for so many of our students. Becoming part of that experience by understanding our shared history can only make us better teachers.

Roberts framed his talk within what he called the “Three Necessary Freedoms” our student population must be able to embrace:

The Freedom to Dream. Our students have often learned through their own life experiences not to dream or imagine a future for themselves. Just the habit of looking forward, of seeing themselves in a better place is one of the foremost challenges of serving students who are at risk of dropping out or who have already dropped out. Finding ways to embrace these students in the first months of their enrollment in a dropout recovery program should include some clear data collection on their sense of hope on entry to the program, and then reaching out with actual exercises in the practice of dreaming and hoping.

The Freedom to Learn. When Roberts was growing up, it was literally against the law for some children to learn. Overcoming that tremendous obstacle became more of a social upheaval than a legal change. Many at-promise students don’t believe or understand that they have the freedom to learn because there have been so many roadblocks in their way up to this point. Many at-promise students don’t have access to learning – either at their own pace, at a pace that meets their realistic lives, or to learn based on what they are interested in, or what is truly relevant to their lives. Finding options and alternative ways to provide these different points of access are essential to providing the freedom to learn for all students.

The Freedom to Achieve. This is the most elusive freedom for students at risk of dropping out and dropout recovery students. One of the major problems, Roberts said, is that these students don’t have access to a realistic understanding of the world. Once you know the realities of the world (the gateways you need to navigate, the roadblocks you can overcome), THEN you can move beyond those realities. He gave the example of raising a child of color to believe that they will no longer encounter racism in a modern world. But then, bigotry harms them when they begin to deal with the real world. Being honest with young people prepares them to move beyond the entrenched and institutional racism they will encounter. As Roberts described it:

“Don’t live in fear of the dragon; go out and meet the dragon, so you know how to navigate the situation and either slay the dragon or find a way around it.”

Roberts also discussed how African Americans have been differentially oppressed. One kind of roadblock to a student of color may not be the same kind another student faces. Similarly, English Language Learners face differential oppression, mixed with the bigotry of anti-immigration politics. Being honest with students is important so that they can not only use their diploma effectively, but know that they will still face challenges once they have achieved their secondary education. Helping them be prepared for those next steps and those realities should be an important part of educating in a dropout recovery environment.

The Crucial Lessons of History & Truth in Experience

Roberts related how we must be careful with truth and with history – those Necessary Freedoms depend upon it. He shared how history is being rewritten to the detriment of all of us. For example: the man who was formerly the student body present of Central High that year of integration (1957) has written that most of the white students totally supported the Little Rock Nine, and in fact had prepared a welcoming party for them! Roberts joked, “it was just too bad that party got canceled!” In fact, that year some white students gave up their right to learn by leaving the school in the name of segregation forever. Often left unrelated in the story of the Little Rock Nine is how a day did not go by that year that each of the Nine were beaten up, abused or tortured by the students and some of the teachers. The Nine were split up and put in separate classes so they never got to see each other or be with each other during the school day and were left to fend for themselves.

Roberts revealed that he’d wanted to quit every day. But he didn’t because of three things: 1) he knew that people had died for him to be able to go to Central, 2) the law was on his side; and 3) he was stubborn! He didn’t have an overall plan of how to navigate that year, but because he had made himself “the executive in charge of his own learning,” he found ways to learn what he wanted to learn. The Nine were aggressively opposed throughout that first year especially, and teachers who might have supported them stayed silent because of the pressure they felt and actual threats they received. The reality is a horrible tale of how humans can be incredibly cruel, and at the same time, how others can be incredibly courageous.

In the end, the freedom to learn and achieve that our students deserve must be taught by teachers courageous enough to teach truth to power and be part of even the most uncomfortable moments of our shared history. After all, those moments have created our present – a present that still requires us to teach for those Necessary Freedoms.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]