Theresa Pogach

Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

Right now, a tab is still open on my browser to a CNN photo gallery. It’s of a 6-year-old girl brutally killed in Ukraine. I didn’t mean to look, I didn’t mean to ignore the “graphic content” warning, or maybe I did. Regardless, now I’m broken. I’ve seen hell in the lifeless eyes of a young girl, and I can say we must get this right. We must make sure the invasion of Ukraine is discussed, dissected, and given the historical context in our classrooms.

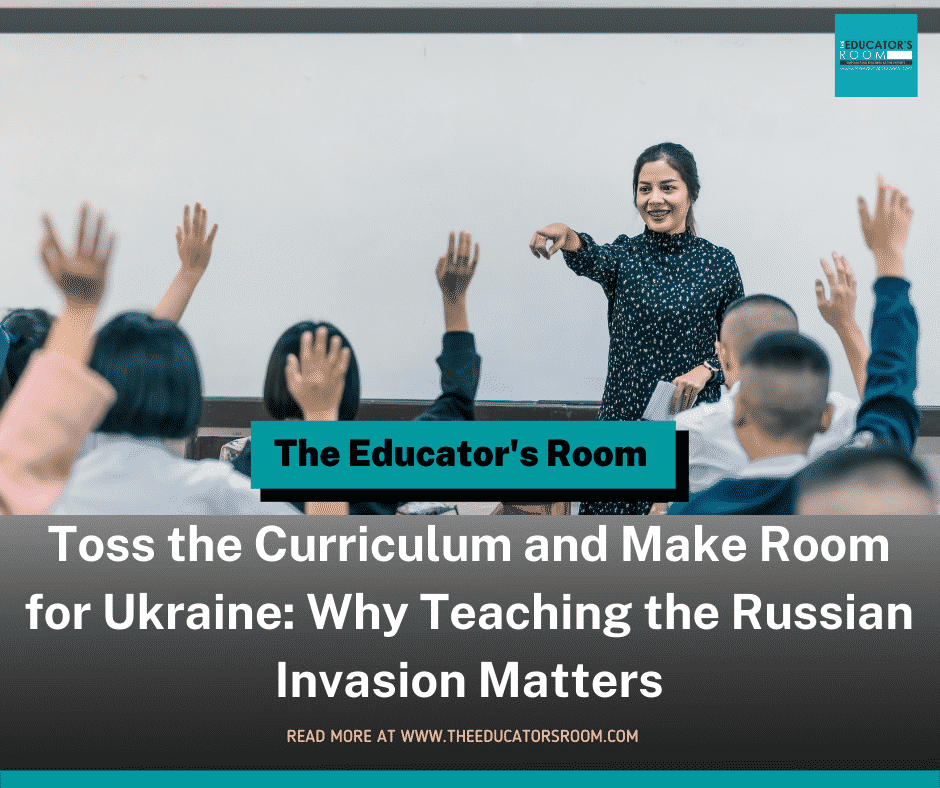

Over the past several days, I’ve realized a few things. One, my middle school students are ravenous to learn about the invasion. They feel the tension as they see adults consume the news. They need to know. They need to understand what is happening, not because they want to do well on a final exam. But because they have random questions about Belarus, elderly men taking up arms, the Soviet Union, and nuclear weapons.

Second, they are ripe for “aha” moments that will impact the rest of their lives. During our lessons this week, students learned how involvement in NATO works and how Ukraine is turning toward the West and away from Russian oligarchies. They learned the details of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, otherwise known as that time Russia promised never to invade Ukraine if they destroyed their nuclear weapons. Ukraine kept its part of the bargain, yet here we are. The United States and Great Britain brokered the deal. So they have skin in the game. Kids have a lot to say about this, and almost all of it comes back to fairness.

I’ve found these lessons particularly vital with students learning World War I and World War II history. They see patterns- they see three steps ahead, and they’re deeply concerned. We dissect why Americans should care about what’s happening in Ukraine.

Putin’s “big lie” isn’t the first one they’ve heard, but it’s perhaps the most outlandish. Accusing a country of genocide and labeling them Nazis as their Jewish president fights for sovereignty reeks of the most flagrant deception. In Mein Kampf, Hitler touted the value of big lies. He claimed they worked better than little lies because people “would not believe others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously.”

Putin is working from Hitler’s playbook and using Russia’s government-run media to spread the lie. Protests in Russia are quickly squashed, leaving the deafening lie to fester, repeated and repeated until it is truth in the minds of his people.

As American educators, we must make time for Ukraine. The 50 states’ capital quizzes can wait, although geography sorely needs attention. One in three Americans can’t find Ukraine on a map. We must make space for Ukraine and continue to update our discussions as events unfold.

Knowledgeable activism is a powerful lesson embedded in this war. In a well-meaning effort to show solidarity, some US states are boycotting or destroying “Russian” vodka. Unfortunately, this knee-jerk reaction is an example of acting before thinking. Or, in this case, acting before doing your research. Smirnoff Vodka, a target of such rebut, is owned by British spirits giant Diageo and is manufactured in Illinois. Stoli’s headquarters is in Luxembourg, and they stand in solidarity with Ukraine. It becomes clear how easily misinformation and assumptions can create unintended consequences. These are lessons you may not find in your planned scope and sequence for the year.

Ukraine is an excellent example of why posting a year’s worth of lesson plans in August is lunacy. It has been said, “We teach children, not curriculum.” We must teach children at this moment and guide them during this time. It’s not a one-off lesson.

We begin each day with a strategic update on the Russian war against Ukraine in my class. We discuss new sanctions imposed overnight and how different media outlets lay blame. We reflect on the devastating choices being made. We’re experiencing it together, learning together, expressing emotions together. Teaching the invasion has brought us closer as a class. While I’ll never subject my students to the images I’ve seen, I will always make room for Ukraine, for freedom, for the blinding light of truth in the face of big lies.

Theresa Pogach is a Middle School Interactive Humanities teacher at AIM Academy in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is a recent transplant from Los Angeles, CA, where she taught elementary school for thirteen years at Village School in Pacific Palisades, CA. Beyond being an educator, she is a passionate student of history and an avid writer. Theresa has a BA in English from Loyola Marymount University and teaching credentials from Cal State University Los Angeles.