Voices off and eyes on me,

in three,

in two,

and one.

The class expectation is 100% engagement while the teacher gives the ‘stand and deliver’ routine for an hour.

G is taking notes in her binder.

And she is one of three students who’s raising her hand and adding insight to the conversation. She is on point, too.

But she refuses to stop drawing with the painting app on her laptop.

G is an IEP student with Attention Deficit Disorder. When she chooses to follow directions and put away her computer, she joins her peers and alternates between the fad of rubbing the silver gum wrappers onto her binder and chatting with her friends.

The expectation was 100%. While drawing, G was engaging at 90%.

But, after she put away her computer? G’s attention dropped down to 50%.

Students like G with IEPs – and their teachers – can benefit from contracts that clearly define what they need to be successful in the classroom.

The tension between expectations and accommodations

Be honest. How many of us miss the ability to multitask as we did during virtual meetings at the height of COVID? We all get restless in our weekly staff meetings. Halfway through most weekly meetings, I give myself a walking break.

But we expect our students to do what we barely can do – sit and focus for long periods and, sometimes, without even the space to doodle.

Even as a special educator and someone guilty of doodling on my colleague’s notes, I have fallen prey to this thinking. I wrestle with the tension between straining with my students to ensure they fit the expectations of what focus should look like and what is more conducive to their engagement.

If we genuinely want to embrace neurodiversity, we need to expand our view of what engagement can look like in our classrooms and start with our students with documented neurodiversity in an Individualized Education Plan.

How do we include the student fully in the general education setting and accommodate these needs?

Case managers can often ease the tension with accommodations by developing, modeling, and communicating how the accommodation should be in practice.

To make it work for the classroom, I often will develop a contract with the student and invite feedback from the general education teachers and the student’s home caregivers.

With neurodiversity, equity doesn’t always mean equal

If students can’t see the board, we move them to the front row.

But when a student needs more stimuli, what do we do?

We tell them to sit down.

Sit up.

Stop doodling.

But according to CHAAD.org, drawing may help a student compensate for the limited stimuli of the typical classroom. When used this way, drawing – like fidgeting – can be classified as “stimming” (self-stimulatory behaviors) or movements/sounds a student creates as a way to enhance their focus.

Psychologist Dr. Carey A. Heller acknowledges that some educators may not understand how stimming can promote a student’s focus, including those with ADHD. She wrote, “Nonetheless, as a clinical psychologist, I have seen firsthand countless times the real impact that harnessing fidgeting can have on people of all ages in improving focus.”

The student as expert on their needs

Of course, we want to educate ourselves and our colleagues on neurodiversity and stimming with experts like reference experts like Dr. Heller.

But who knows your student best?

Seek out the ultimate experts – ask the student and their home caregivers what might work for them, consider all reasonable options and discuss which one(s) to try.

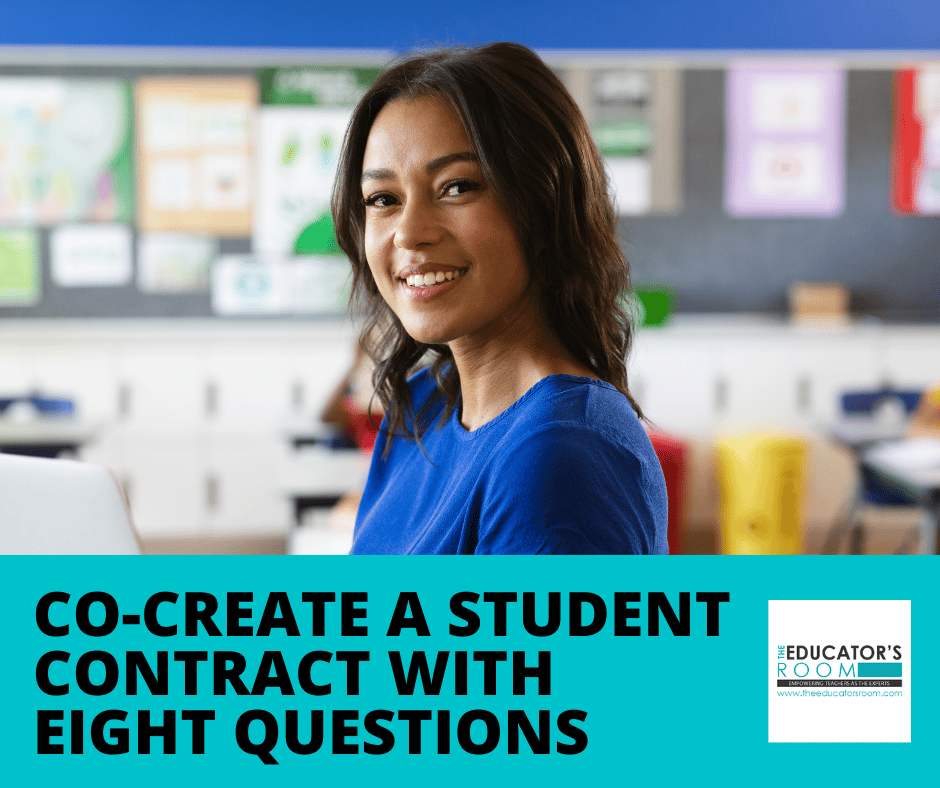

Break the tension by co-creating a student contract

When co-writing a contract with students and their teachers, I use these guiding questions with the team:

- How should the accommodation look? (E.g. Is the student allowed to draw with paper and pencil? Markers? Computer?)

- When will the student have access to the accommodation? (E.g. During lectures? Upon work completion?)

- What are the student’s responsibilities? (E.g. Sharing completed work with the teacher and seeking permission to draw?)

- Which other limits are in place? (E.g. Is the student expected to draw without engaging peers?)

- How will the teacher approach redirection when the student does not meet guidelines? (E.g. A two-minute warning?)

- What are the consequences if the student continues not to follow the guidelines? (E.g. Limiting drawing to paper rather than the computer? Informing parents?)

- What are the teachers’ responsibilities? (E.g. Should they approach the student or case manager with concerns or suggestions?)

- When and how will the student and the case manager review the contract and determine its effectiveness? (E.g. Grade reporting? Teacher feedback?)

Once I have developed a contract with a student, I empower them with the responsibility to review it with their parents and have themselves, their parents, and their case manager sign it.

The Results

Using the eight questions, G and I developed the contract together, and she was positively engaged with it. She had reasonable responses and was really amenable to compromise.

In the past, I have seen significant success with student contracts – especially when the student is involved directly with developing it – and so far, G is holding up her end of the deal. One of her teachers just wrote a positive email home about her progress!

Kimberly Cecchini is an educator, writer, and filmmaker who believes in making clients, students, and collaborators feel understood and empowered. For the past two decades, she has taught middle school inclusion, resource, and self-contained middle school classes. Kimberly believes relationships and creativity are at the core of helping neurodiverse students be successful. Originally from New Jersey, she currently lives in Seattle and teaches middle school students. She lives with her spouse and loves hiking, kayaking, reading, and drawing.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.