How to Use Visual Texts in the ELA Classroom

Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

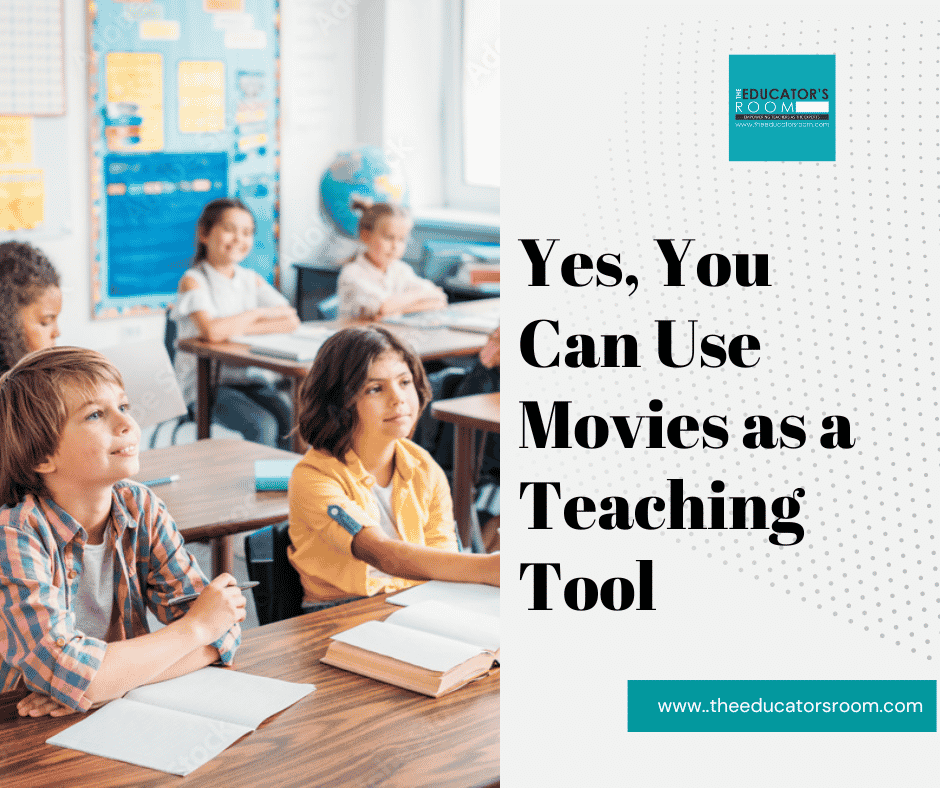

I’m sure they’re out there, but I have yet to meet the student who insists on reading the book rather than watching the movie version of a story. That said, as a lifelong book lover and believer in the value of the written word, I will never agree that movies and visual texts should replace books. However, there is value in including film and visual texts in the ELA classroom. In fact, it could be the hook that gets your students excited about iconic and important texts.

Graphic Novels: Not Your Mother’s Comic Books

For learners of all levels, but especially for students who struggle or hate to read, visual texts can introduce them to the world of literature in an accessible way. Graphic novels (we used to call them comic books) rely on both words and images to convey a story. But don’t let the pretty pictures fool you. Today’s graphic novels require as much if not more focus and engagement. Not only must students read the words, but they must also interpret the images–the facial expressions, the body language, the positioning of elements in a frame–and integrate all of that into their overall comprehension of the story. Students must interpret details like subtle color shifts or the tiniest raised eyebrow. Graphic novels also portray complex issues in deceptively simple ways so that kids can grapple with profound concepts without feeling like it’s work.

For example, my middle school students often confused the characters in George Orwell’s classic Animal Farm. Given the allegorical nature of the text, it’s vital that kids understand why Snowball was scapegoated. The graphic novel helps kids distinguish between characters so that they can access the important themes in the story.

Until recently, I had always assumed that my students were like me: they pictured the story and imagined the characters as they read our class novels. When I learned that this was not the case, it changed the way I approach all of our readings. Our students are growing up in a different time. Their world is much more visual, much more digital, than ours ever was. For this reason–and because we know attention is at a premium–visual texts really must become part of our ELA offerings.

We elevate the classics because they remain relevant; they’re part of our culture. But when a student with limited English skills or impaired eyesight enters my classroom, it’s important that the texts we use are accessible without losing the very thing that makes that story so important.

Graphic novels work as both supplemental and primary texts. Notably, they open the door to what we are really hoping to achieve: access to the most important ideas and stories of our time.

No, We’re Not Watching the Whole Movie!

Because some of our students simply don’t generate the images of a story as they read, films and film clips can provide them with the pictures they need to more fully engage with a text.

Movie trailers are a great way to get kids excited about a story, but they can also be used to elicit engaged writing. When students “read” a movie trailer–much like the seemingly effortless work they do when reading a graphic novel–they are immediately categorizing, inferring, comparing, and integrating dozens of bits of information. What’s great about movie trailers is that they are immediately engaging: the sound, the action, the tantalizing teasers.

In my Film as Literature class, we use movie trailers to decide which films in a particular category we should watch. This student-choice activity seems innocuous, but it contributes to the investment kids have in their learning when they’re the ones deciding which film best represents a particular concept or technique.

Movie trailers can also be used for prediction exercises, to elicit evidence to support a thesis, and to make comparisons. It’s far easier to discuss a director’s intentions, given all the visual and auditory evidence a movie trailer provides than it is to ask students to extrapolate an author’s intentions when there is so much more to reading than just visual cues. Movie trailers can give kids confidence that they are developing a skill that works in tandem with their reading development.

In the past, films were often shown as a reward: We will read this book and then watch the movie. Comparisons between the book and movie versions may have been made, or the movie was the carrot dangled to get kids to read. With the kind of movie access kids have now, we’re kidding ourselves if we think our students aren’t going to reach for the film version of a class story or book. If we are deliberate about the way in which we use these visual texts, and if we treat them with the same intention that we do our written texts, we meet our students where they are.

Art Is Reading!

On first glance and especially with younger students, it may seem that artwork is a separate and distinct medium with its own unique skills. Yet just like the creation of a story requires intention, an awareness of the audience, a purpose, the same is true for works of art. An English language learner can access complex ideas through artwork much more quickly and accurately than they may be able to in the initial stages of their English language acquisition.

Interpreting art isn’t just for ELLs, though. Using art in middle and high school English classes not only exposes students to important works of art. It also asks them to employ all of the skills they use when they read: infer, predict, hypothesize, support. Art is a terrific alternative to the traditional writing prompts, too. Students can use art to inspire writing, to describe what they see using more nuanced vocabulary, or to extend the story that a piece of art tells. As their confidence and creativity grows, students can move beyond interpreting the realistic to the impressionistic to the abstract.

A class favorite is Steve Cutts, whose images of modern society make clear and critical statements about the way we live and what we value. After working through some of those images, students are better equipped to study the messages that artists like Magritte and Dali were trying to convey. While they must use visual evidence to support their conclusions, they enjoy the activity because as long as they have support, they can’t be wrong.

Our Students’ World Is Visual

The world of discovery for our students is instantly available on their cell phones. They can watch YouTube videos to learn almost anything…on the surface. Countless websites summarize texts, provide complex themes, and offer background information on important books so that kids (and adults!) don’t have to read the whole thing. But without us to guide them to look closer, think deeper, notice details, they will skim the surface of knowledge without gaining any real wisdom.

Our students’ interactions with the world and one another are not only digital, they are visual as well. Even assembly instructions now come without words. That’s why it’s so important to integrate visual texts of all types into the ELA classroom. Our students are going to access those ideas anyway. If we are there to guide and suggest, to challenge and advance their critical thinking, we are not only meeting them where they are; we are asking them to reach further.

Laura Sofen has been a middle and high school English teacher for the past 20 years. Prior to that she worked in publishing and corporate communications. She is an avid reader, hiker, traveler, and dog lover.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.