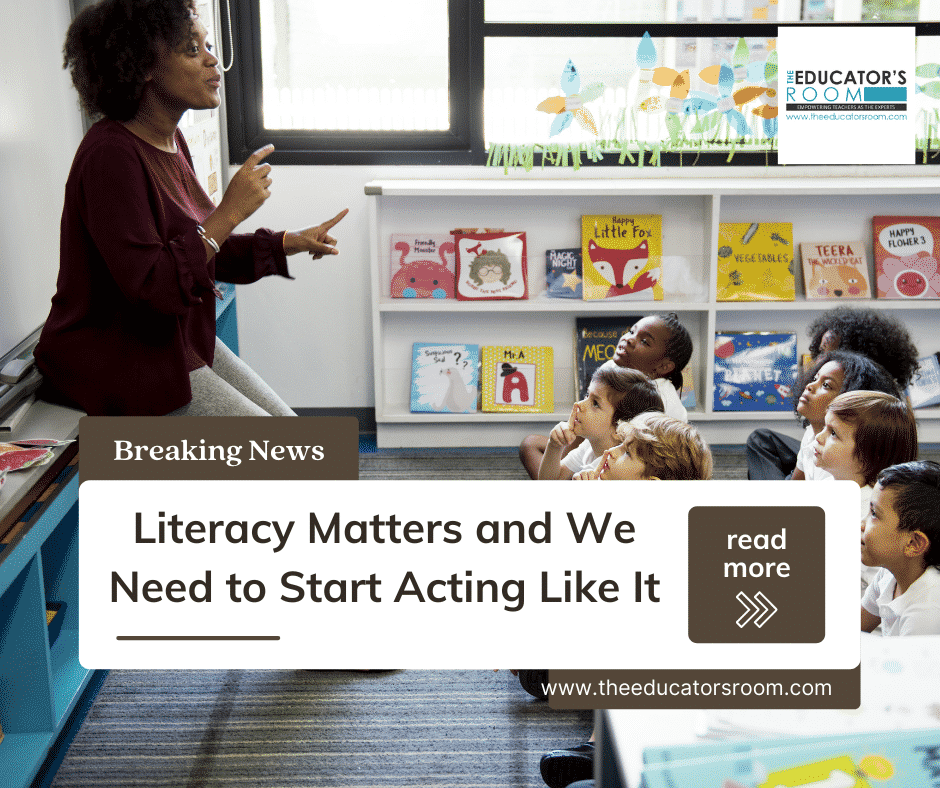

The aha moment hit me nearly two months too late. For weeks, I had been working with one of our SPED teachers to figure out how to get students to turn in their work. After years of effectively managing my classes through meaningful work with clear deadlines, I was overwhelmed by the number of student behavioral issues. I worked hard to simplify the assignments and make the novel we were reading accessible to them, but I had been truly reaching the end of my proverbial rope.

At the end of the unit, the two of us looked at each other and clarity hit: my students were seemingly unmanageable because they literally could not do what I was asking them to do. Most of their literacy skills were too weak and their frustration was spilling over into their behavior. I felt the overwhelming urge to make immediate changes to accommodate the needs that were staring me straight in the face, but I faced a series of roadblocks from the top to the bottom that pushed most of those sweeping changes out of reach.

It was a real-life example of an uncomfortable truth: most people can agree that reading and associated literacy skills are important, but few want to make the sacrifices necessary to help that happen. Strong literacy skills impact the study of every subject from the time our students are in Kindergarten until they graduate from high school.

And this matters too much to not make this one of our top educational priorities.

So if it is so necessary, what do we do about it?

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to our national reading deficit. We are dealing with students with multiple learning styles and needs and challenges only compounded by two years of pandemic-challenged education. But while it often feels like teachers have a mountain to climb, we do need to start somewhere.

Students need time.

We need to take away the excuse of “I’m too busy,” and give children the time and space to read and explore and learn to love the written word again. Students at all levels, from elementary to AP English, should be given a set time every week to read in their English classes. They should be allowed to read any book they want, from The Diary of a Wimpy Kid to manga comics to Charles Dickens. Let them be challenged and let them embrace nostalgia. Yes, it’s sometimes hard to watch my AP students pick up the graphic novels that I have set aside for my struggling readers, but my primary concern is that they are reading. And what am I doing during those reading minutes? I’m reading with them. I’m modeling the behavior that I expect from them.

What about “lost” instruction time? Is it really “lost” if students are building reading skills and stamina and practicing a skill that we need them to do in order to be successful in our classes? I would argue that the answer is “no.” Students don’t need to do another worksheet. They do need to read.

Students need to be met where they are.

Rigor is a simple buzzword that people often use as an alternative to difficulty, but rigor instead should be intended to ask students to reach higher. Solid reading and writing instruction will ask students to climb manageable hills, not Mount Everest.

When we recognize students struggling, they should receive immediate intervention instead of just telling them to keep trying harder. In a system that is bleeding out teachers, this becomes even more difficult. Most teachers don’t have the time to effectively identify reading issues and then deal with them on a one-on-one basis in overcrowded classrooms. Most schools cannot afford reading specialists to deal with students who struggle on every point of the learning disabilities spectrum. But if we truly believe that reading and writing skills matter, we need to do everything possible to help these students as soon as possible. This should also be one of the first potential issues we look at when a student displays problematic behavior. This early intervention and meeting them where they are could help alleviate a host of immediate problems and issues down the road.

Teachers need to be seen as experts.

We need to stop seeing preschool teachers as glorified babysitters and instead train them to be well-paid early childhood literacy experts who understand how to expose our little learners to language. We need to allow our Kindergarten teachers to get back to play and exploration with easy access to picture books and early readers in the classroom for those who are ready. When middle school teachers allow their students to do book reports and projects over graphic novels, we should praise them for meeting their readers where they are. And when high school teachers argue that English class isn’t about learning the classics but about teaching students lifelong literacy skills that will follow them to either college or their future careers, regardless of a student’s future vocation, we should regularly show teenagers how that is true in our own lives.

Teachers also need to be encouraged to live out the importance of literacy. Books, audiobooks, podcasts, and diversity in our news sources should be a regular part of our lives. We should read the books our students are reading and be willing to engage them in discussions about their favorite texts. Reading and writing shouldn’t just be for homework completion, they should also be a part of students’ lives outside of the classroom and they need to see us doing the same.

When I discuss our national literacy deficit, I often feel like Don Quixote. I want to slay the giant when others just see a harmless windmill. But I refuse to believe that all hope is lost. Like nearly every other issue in education, we just have to decide that it’s a problem worth fixing.