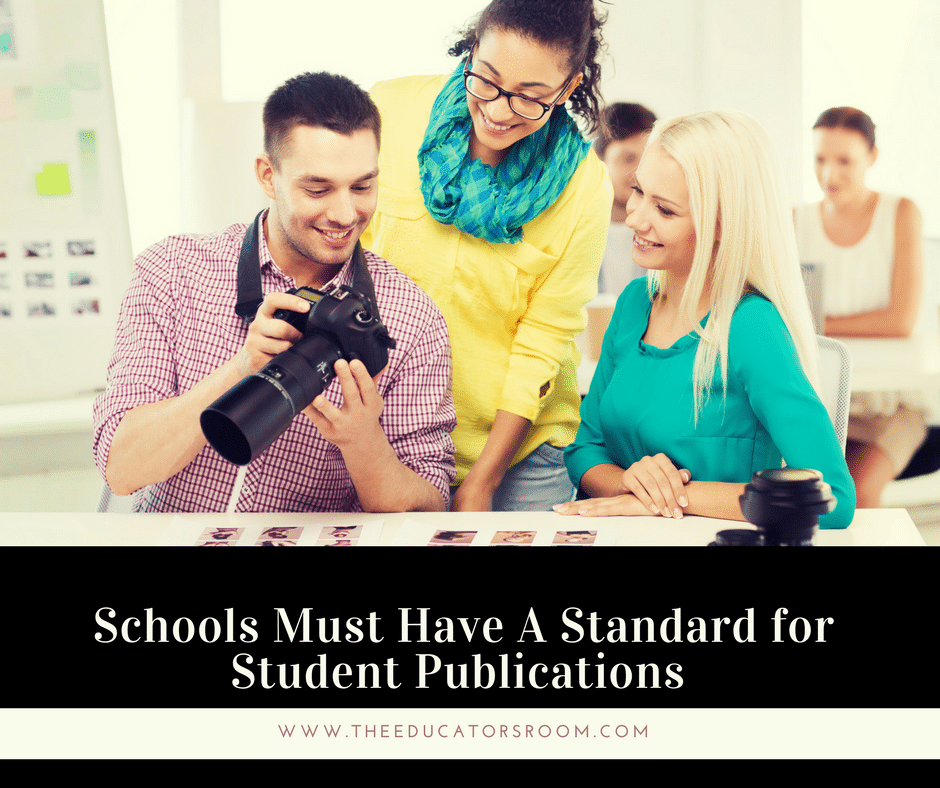

This time of year is the worst time for a journalism advisor. The campus yearbook, the school’s biggest group project if you really think about it, is finally distributed for the school and community to see after months of intense creative designing, photo editing, late night work sessions, and high-pressure deadlines, all to selflessly chronicle the school’s year.

A journalism program is unique in the sense that student’s homework is publicly shared and up for criticism. Those criticizing forget that these are still children and we are still a school, whose purpose is to educate. More so, a journalism advisor is always walking on egg shells – a publication that may offend just one person can cause us our jobs, even though its intent is good or whatever being published is rooted in fact.

It never fails that around this time, yearbook articles begin to emerge: parents upset over a LGBTQ-themed page, books recalled over a bad cover, and a student suspended over a submitted picture.

The one that has made the most headlines this year is a yearbook editing a student’s picture to take out a Trump campaign logo. The school decided to reprint all the yearbooks and suspended the adviser.

And every year, the question always arises: should student journalists have the full freedom of the press? Should students have full freedom of speech?

[bctt tweet=”Should students have full freedom of speech?” username=””]

This issue has already been addressed by the Supreme Court.

Journalism students and teachers go over numerous court cases that involve free speech and free press, but two – among others – have set precedent when specifically discuss school publications.

In the case of Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, a group of students wanted to write a story about divorce and pregnancy at Hazelwood East High School. The divorce article featured a story about a girl who blamed her father’s actions for her parents’ divorce. The teenage pregnancy article featured stories in which pregnant students at Hazelwood East shared their experiences. Although the names of the students were kept private, the school principal felt that the subject was inappropriate.

The court concluded that a school, within reason, as the right to censor student publications sponsored by the school which are “inconsistent with the shared valued of civilized social order.” More so, the court said that the newspaper “was not intended as a public forum in which everyone could share views; rather, it was a limited forum for journalism students to write articles pursuant to the requirements of their Journalism II class, and subject to appropriate editing by the school.”

Secondly, in the case of Tinker v. Des Moines, students organized a silent protest against the Vietnam War. Students planned to wear black armbands to school to protest the fighting but the principal found out and told the students they would be suspended if they wore the armbands.

The court ruled in a 7-2 decision in favor of the students. “Students don’t shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gates,” they concluded. More so, the case also said, “for school officials to justify censoring speech, they must be able to show that [their] action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.”

Let me preface by saying, as a journalism teacher in the state of Texas, I am all for student journalist being fully protected under the first amendment. I wish we could publish what we want. However, I am a teacher first and a journalist second. The goal, at the high school level, is to teach the proper journalistic standard, as well as protecting the student journalist and the institution. If that means to not allow students to publish an article that may cause harm to the school or their credibility, then as the gatekeeper, it will not be published. After my first year of being over the journalism program, it was essential that I put the publication’s standard for the campus in print.

In the case with the yearbook editing the Trump logo, it was an edit that many journalism advisers would probably make themselves, in an effort to keep a standard with all other student photos in the book. Bucking the school and the adviser, making the district reprint the books, and the district suspending the teacher for making a good decision, is another example of schools continuing to lose their authority in the community, a continued sense of entitlement, and the idea that everyone gets a trophy if they complain.

Needless to say, the standard for all school publication needs to be printed in the district’s student handbook, which the students and the parents sign. This is a valuable lesson for all students, teachers, parents, school, and communities.