It was year five in my teaching career, and our principal called us in to bemoan our writing scores from the previous year. It was all the same buzzwords (fidelity, accountability, etc.), and I remember asking a question that changed my teaching beliefs.

“If we want kids to be better writers, why aren’t we making our schedule to reflect that?”

This was an innocent question because I was stumped on what I could do differently with 150 students daily in 55-minute class periods. Luckily, my principal was new and was interested in having “great data,” so instead of being defensive, he listened to our ELA department’s suggestions, including:

- Changing our schedule to 90-minute blocks

- Giving the ELA Department time to create a writing plan.

- Investing in the professional learning of all our teachers about how to teach writing.

So, for the next eight years, as our team changed and educational jargon increased, we put reading and writing first, and we saw significant gains in helping kids become better writers in high school.

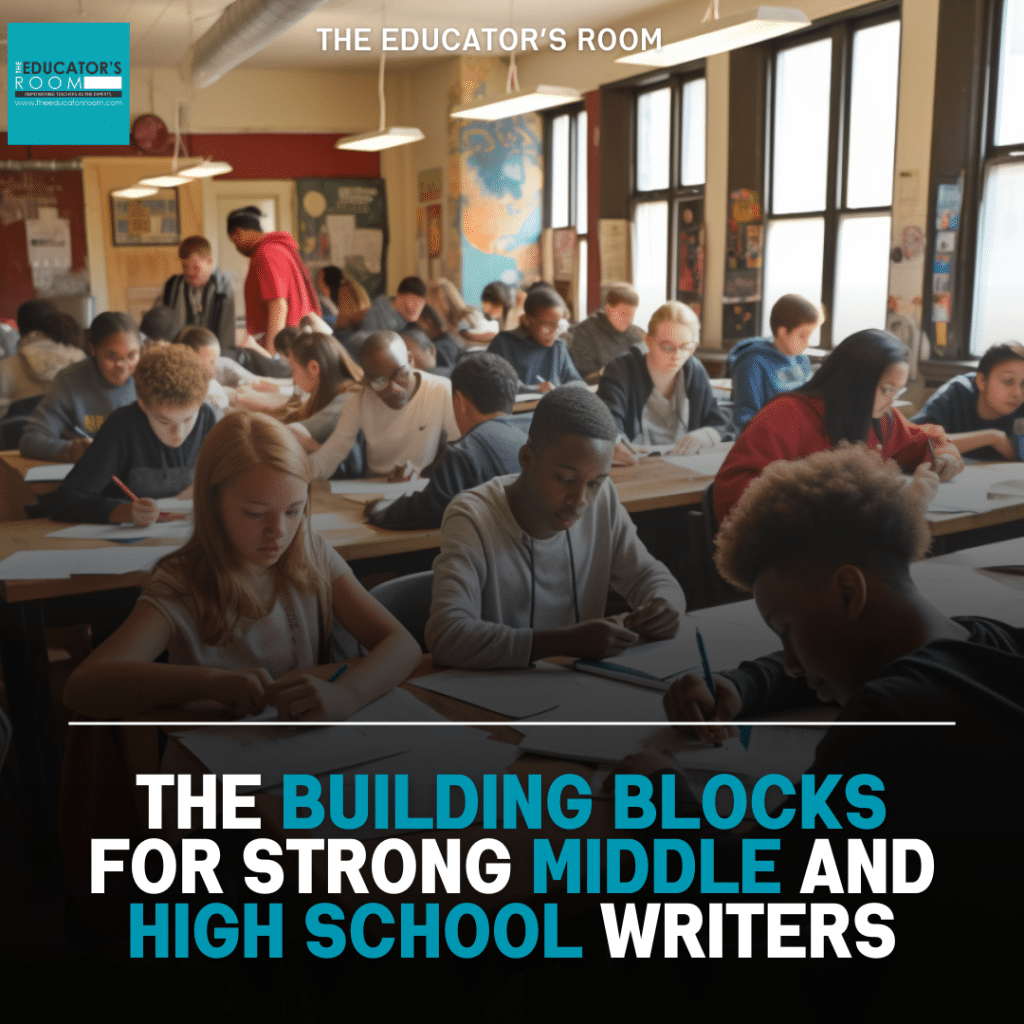

Middle and high school students do not become proficient writers by osmosis- it is a process that can take years to develop. However, there are building blocks that can help a teacher, school, or system start the process sooner rather than later. During our first planning meeting as a department, we spent a significant amount of time discussing our goals, and we kept revisiting the word “proficient” when referring to the level we desired all students to achieve. Ultimately, we wanted every child to be able to communicate their thoughts to a variety of audiences effectively.

However, teachers’ use of more extensive and intensive writing experiences in secondary classrooms was infrequent – at best.

Looking back, here’s what we embraced at our school that helped make our work intentionally guided by evidence-based practices.

Writing Starts at the Sentence Level

Writing a sentence is one of the first things students learn after they learn to write their name and address. As a team, we realized that many kids struggled to write a complex sentences on paper. It wasn’t because they could not talk but because they relied on writing how they texted on their electronic devices. Combined with the lack of explicit grammar instruction due to an emphasis on test prep in elementary schools, our students needed a lot of work. A study by Macken-Horarik et al. (2018) found that Australian teachers overwhelmingly believed teaching grammar in context was important (83%).

We all agreed to give a grammar Pre-Test to see what our students knew. Some of us wanted a paper copy while others used an online one, but every student took it, and we created a mini grammar scope and sequence based on our grade levels. In ninth grade, we almost always started with reacquainted students with the basic eight parts of speech, then subject-verb agreement and complex sentences, and eventually, in the second semester, we attempted to diagram sentences.

The lessons were embedded into our daily lessons, and students practiced writing sentences with their learned skills. We kept a notebook of grammar rules and stayed under 20 minutes daily for playful and engaging lessons. Students complained, and parents thought this was too “elementary,” but when we shared our vision for the end of the year, they reluctantly agreed to “trust the process.”

For schools that are seeing significant gaps in grammar skills for their students, here are some questions that schools/teachers can think about as they teach their students these important skills:

- What do my kids know regarding grammar?

- How can we give students consistent practice with grammar?

- What grammar resources do we have for students and teachers?

- How can teachers make the content engaging?

- What digital tools can help grade and give feedback on grammar?

Writing instruction should be explicit

During our meetings as a department, we had to confront the fact that we just assumed kids could write, and that explicit instruction was lacking. We had some teachers who provided a lot of support in writing and others who just assigned it. To level the field, we spent a significant amount of time really developing our writing assignments and the explicit instruction needed to help students and increase their self-efficacy.

Closing the gap required us to develop the school’s writing instruction and implement a writing portfolio for all students. Instead of just completing tasks never to revisit, they spent time revisiting assignments and seeing feedback as a gift- not a grade. In my ninth-grade classroom, we started to learn what good writing looked like and annotate the various features. I reiterated that writing starts at the sentence level. We spent time writing complex sentences and using those to develop paragraphs and then multi-essay writing. The more we wrote, the more feedback I gave, and the more I asked students to continue to write.

As we made writing more explicit in our English/language arts classrooms, here are some questions that schools/departments/teachers can think about:

- What curriculum will we use to teach the elements of writing explicitly?

- If there is no curriculum, have the grade-level teachers planned their writing units to build their assignments?

- What are the big writing topics that need to be covered? How do those topics support the reading students are doing?

- How is writing graded? How is feedback given to students? What rubrics will teachers use to give feedback?

- How can we build in times for conversations about writing?

Reading is just as important as writing

Kids who read have a window into what proficient writing looks like. They can use it as a reference point for structure and as a window to show what is happening in their world. When building a writing culture in your school, just as much time must be spent on developing readers.

This includes giving students time to read in class and time to talk about what they are reading. A culture of reading is less worried about students’ level- yes, they have a place- and more worried about developing readers who can think and read critically.

Some questions that schools/departments/teachers can think about are:

- Do we have a functioning library? Do we have a librarian who can help find the “right” book for every kid?

- Are we updating our Youth Adult Literature for titles that interest our students?

- Are we setting time for kids to read uninterrupted? Are we conversing about kids’ strengths and weaknesses in reading?

Conversations move learning forward

A classroom with a positive dialogue between students and their teachers is one where feedback can be received and given. We noticed that while many students did not write, the ones who did were compliant and did it for a “grade.” To shift perspectives, we focused on drafting writing (pre-writing, drafting, feedback, drafting) and stressed that most writing can be revised. Students began to draft their writing in class.

During this drafting time, students could be doing three tasks simultaneously around writing: writing, discussing, and collaborating. The writing is self-explanatory, but I encouraged students to draft on paper to avoid the distractions of electronics. Students could ask their peers or teachers questions about what they write, which can lead to collaboration. During the collaboration, students are asking for feedback and actively working to gain clarity and feedback and internalize how to improve their writing. The process is continual, and while ultimately, a grade was given for a final copy, it did not come without weeks of getting better.

As students are in the drafting phase, it is critical for schools, staff, and teachers to think about this:

- How will I incorporate time for actual writing in my class?

- How can I examine the writing students must master before their next school year?

- How can I teach students about receiving and giving feedback?

- What resources do I need to help students use drafting time in a way that helps them?

Using these building blocks sets the stage for the grading to be a formality and not the end destination for students and teachers. It also gave them the much-needed practice to better their craft. As schools look to improve their students’ writing skills further, these building blocks can help move the needle more purposefully.