Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

I remember the first time I questioned whether a student paper was actually theirs. In an age before advanced plagiarism checkers, a colleague suggested that I Google a key phrase from the paper. I put the phrase in quotation marks and, within seconds, had the entire student essay sitting in front of me on the screen. My student couldn’t believe I had so easily discovered that they hadn’t done the work, underestimating two key facts. First, writing teachers quickly develop a keen sense for their students’ writing style. Second, we have the same technology at our fingertips as our students, and that technology has often helped us stay one step ahead of our students and their writing production.

But now teachers have a new apparent foe on the horizon.

It’s common for teachers to find new technologies threatening. I’ve always called my computer my best friend and worst enemy, depending on the day and time. But now teacher chats, particularly those involving teachers responsible for writing instruction, have become consumed by concerns about how ChatGPT, an AI program capable of using natural language to write complete essays.

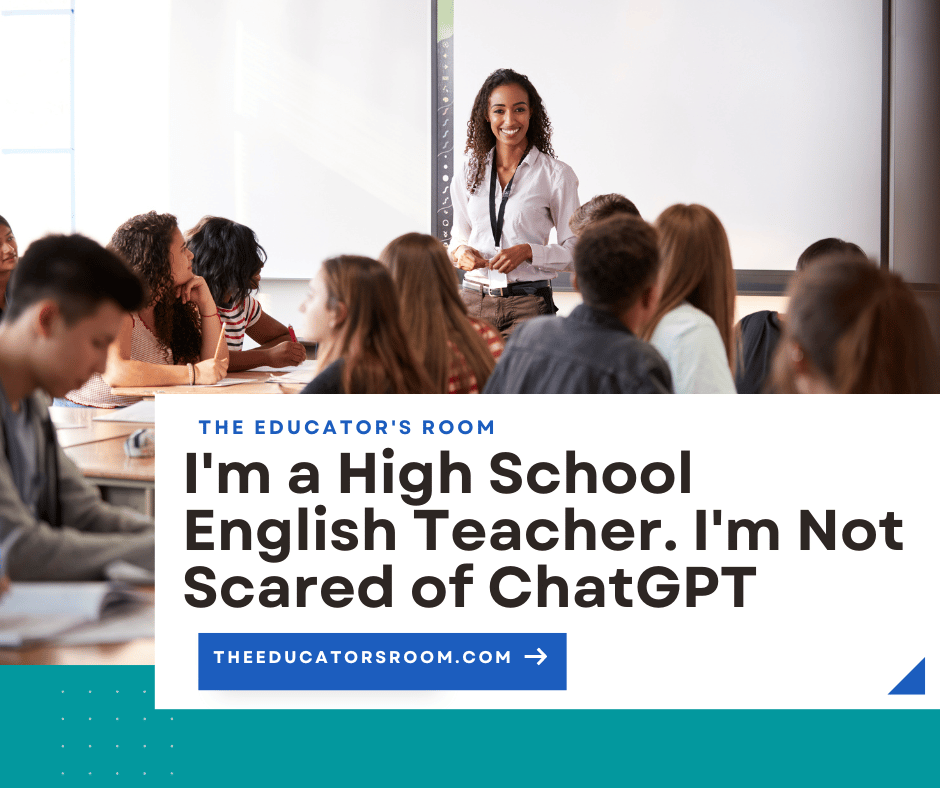

As a 20-year high school English teacher, I share the concerns of many. However, I believe we need to proceed with caution as we process what this means for education, writing careers, and the marketplace of ideas.

Where should we start?

Remember, “perfect” writing is not “good” writing

Good writing makes us think. It appeals to our emotions and awakens our senses. Whether fiction or nonfiction, it synthesizes our human knowledge and experience and challenges the reader to do the same.

Yes, we need to have a serious discussion about the lack of writing skills that we see in our students, K-12 and beyond. It’s not just a lack of basic grammar and mechanics. Readable sentence structure, clarity of ideas, and enhanced vocabulary are missing from the majority of student essays. Sometimes they know what they want to say, but they have no idea how to say it. But if we want them to be expressing their own ideas in their own voice, accepted use of a tool such as ChatGPT will stand in their way.

As Stephen Shankland of CNET argues in his latest piece, “It’s an AI that’s trained to recognize patterns in vast swaths of text harvested from the internet…The answers you get may sound plausible and even authoritative, but they might well be entirely wrong.” AI can give us algorithm-driven correct writing, but it denies the reader an authentic voice and even factual truths.

As I played around with the program, I put in a prompt from my experience as an AP English reader just to see what the AI pumped out. While it gave me four very well-written sentences, it was far from a complete essay. It also lacked the personal experience and insight I appreciated from the best essays I read during that time. The perfect AI grammar and spelling lacked the engaging features of some of the best essays I read during that week. We need to focus on how to translate this important lesson for our students.

Writing instruction needs to improve, period

We’ve known for years that students have struggled to produce meaningful writing. I’ve attended workshops, read books, discussed it on Facebook and Twitter, worked to implement new strategies, and instead of seeing student writing improve, I’ve only seen it get worse. And no, I don’t believe that this is the fault of students depending on their cell phones for communication.

One fellow teacher shared her theory on the biggest drivers behind lost eloquence in student writing. She argues, “standardized testing has shifted the focus of education from generating knowledge to regurgitating knowledge in a standard format.” While testing isn’t the only culprit, it certainly doesn’t help teachers engage their students in writing that matters to them. If we don’t want students to find AI so alluring, we should assign writing that shows students the power of written expression.

If writing matters for the human record and communication of diverse ideas, then we need to address the reasons why so many students struggle with writing in the first place. Our discussion shouldn’t be centered on whether or not AI is going to make our jobs meaningless; it should be centered on why writing instruction matters regardless of a student’s academic future or career plans. As Daniel Herman argues in The Atlantic, “if most contemporary writing pedagogy is necessarily focused on helping students master the basics, what happens when a computer can do it for us? Is this moment more like the invention of the calculator, saving me from the tedium of long division, or more like the invention of the player piano, robbing us of what can be communicated only through human emotion?”

I would argue that it’s a little bit of both and how we proceed matters more than the technology itself.

But if the kids can’t read, ChatGPT doesn’t matter

First, students who cannot read cannot write, period. Second, if they do decide to cheat the system by using tools such as ChatGPT, but they cannot read and understand what the AI produced, then we have bigger problems.

As I played with ChatGPT, something else became painfully apparent to me: many of my students wouldn’t understand what the program wrote for them. They might be able to see that it looks good and even sounds good, but if I asked them to explain what it meant, they wouldn’t know where to start.

Instead of having a panicked conversation about what to do now that a computer can do all of our students’ work, maybe we should be having an in-depth conversation about the greater role of literacy in our student’s education. Maybe we should be talking about the importance of turning our students into good readers who understand what good writing looks like. Good readers become informed citizens who are able to synthesize information from a variety of sources and come to a nuanced understanding of the issues that face them and their neighbors.

Are there reasons to be concerned? Yes, but not because English teachers are worried about losing their jobs. The ability to read and write was one of the most transformative innovations in human history. For thousands of years, this ability has been responsible for the advancement of entire civilizations. Communication matters. Ideas matter. The ability to think for ourselves and communicate those ideas with a broader audience matters.

And computers can’t do that. Yet.

Conclusion

Instead, we should continue to fight for our students’ overall literacy education. In his The Atlantic article, Stephen Marche argues, “In a tech-centered world, language matters, voice and style matter, the study of eloquence matters, history matters, ethical systems matter. But the situation requires humanists to explain why they matter, not constantly undermine their own intellectual foundations.” Whether AI becomes the “calculator” or the ”player piano” of writing depends on how we move forward as both teachers and writers.

So I’m not worried about ChatGPT yet. My students who are desperate to turn in writing without doing the work themselves just have another tool at their disposal. I worry more about my students’ ability to read texts with complex, nuanced ideas and come to their own conclusions. I worry more about their ability to express those clearly and concisely express those ideas. And I worry more about creating an education system that prepares students for the workforce, higher education, and meaningful citizenship.

And if ChatGPT actually forces us to address those profound challenges in our education system, then that realization is enough to make me hopeful, not fearful, for the future.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.

Great piece and an important perspective. I taught middle and high school English for 12 years, and my greatest challenge (and greatest victory, when it happened) was to find or create authentic writing experiences for young people–the opportunity to express ideas that mattered more than a letter grade, to an audience that lived beyond the school walls. ChatGPT is a red herring, as Sarah states–the real issue is how we can design our classrooms in a way that helps our young people develop the skills and confidence to express themselves with power and grace.