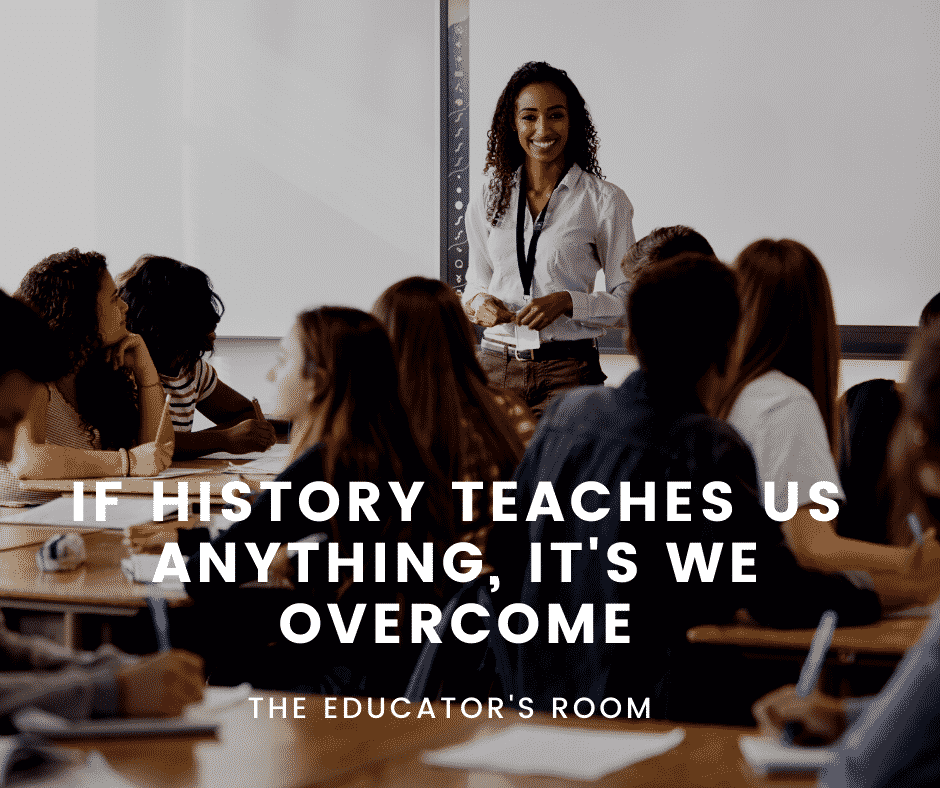

I teach American history most days to an engaged, amazing group of students. But this week, they didn’t want to engage in history; instead, they want to engage in the present.

These 8th-grade students have plenty of questions, as many of us do. There are some who shared they have family members with COVID-19 – one in Chester County, PA, one in Italy – and want to know what happens next. A few have family members traveling in Europe and are now working their way home. Some who relate the suspension of professional sports and the shutdown of Broadway to the clearing of their own extracurricular schedules. They see their older siblings’ college classes convene online and close only to watch many of their own schools join them. Most selflessly worry about their grandparents.

Some joined me in watching the Wall St. rollercoaster ride, astounded the Dow Jones could have its 4th-worst day in history only to be followed by its best. These students, usually eager and jovial, are simply in a common consensus of confusion – asking “what’s next?”

But I’m not sure we’re all that different from them. I’m struggling as a 37-year-old to make sense of it all. But as I looked out into the sea of desks and saw 14-year-olds struggling much more, I shared three lessons I wanted to implore for both them and myself:

1. Be factual, not hysterical. There are so many stories that have been perpetrated by misinformation and a lack of credibility. “I heard this is happening” isn’t credibly corroborated by science or sources. Just as when I taught in a classroom with no window and students would say “there’s an early dismissal,” the first thing I would do is look out the window for snow. And, much like a snow day, many folks seem to have a criticism for those making the decision.

In a world where some feel “facts are in the eye of the beholder,” we need to dig to learn and be critical before fanning the flames of false narratives. We also need to value and support trusted, investigative journalism – including your local news sources. Otherwise, we’re dealing with the wrong thing going “viral.”

[bctt tweet=”Otherwise, we’re dealing with the wrong thing going “viral.”” username=””]

2. Control what you can control. On a small scale, the simple solution to regulate personal health is simply washing our hands and disinfecting surfaces regularly, avoiding people who are sick, and staying home if we’re ill. Every company and campaign has informed you of these not-so-radical measures, and we need to assume personal responsibility.

On a larger scale, there are many difficult decisions that are being made for us, with pretty much every public gathering shuttering its doors. Work schedules are cleared, and people fear not just the spreading COVID-19 but keeping the lights on. Push your elected officials to learn your story and to dedicate our resources in ways that will really help. Support those in your community who are sick or just worried sick. Be a smile that can last a while through this struggle.

3. This has happened before, and we will overcome it. I teach about the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-20, which is probably the most difficult problem that most of us have never heard of. While World War I took the lives of approximately 40 million people, that strain of H1N1 following the war took the lives of at least 10 million more, maybe twice that number. The worst-hit city in the United States was Philadelphia, and that’s largely because the mayor refused to cancel a bond fundraising parade and later nearly 3,000 people died in a week. Remember that when every decision to delay or dissolve an event seems draconian. It’s hard to tell if this amount of devastation would be replicated with COVID-19, but this is where smart decisions now provide plenty of positive dividends later. Those same smart decisions helped quickly curb the most recent strain of H1N1 (swine flu), as well as SARS, Zika, and Ebola outbreaks that have all occurred in these 14-year-olds’ lives.

Smart decisions now provide plenty of positive dividends later.

The American way is to build a community in times of trial. We historically have not retreated and scrambled for every 24-pack of toilet paper on the shelves. Instead, our history teaches us we have cautiously walked hand-in-hand through struggle, even if saying this today is more metaphorical than literal.

Americans don’t just take photos of what we don’t have on the shelves, we are thankful for what we have. If we make these things our priority, we will persevere. And sometimes we need to just pause and regroup to remind ourselves – and teach our children – that America is filled lessons of endurance.

Jake Miller is a middle school history teacher in Central Pennsylvania. His work appears in a variety of local and national periodicals. You can contact him at Jake@MrJakeMiller.com.