[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Like it or not, teaching is a political act. We influence developing minds daily, aiding in their structure of morality and empowerment; and we are embedded in a highly politicized arena ripe with unions, public funding, and arguments over tenure, teacher pay, and pink slips. Yet we often feel “called” to do our work for love of the next generation, and the desire to correct injustices we see in the world.

“Social Justice Education” has swiftly entered the teaching jargon – but what does it even mean? Of course you’re all about justice, and you educate! Right? But if we take the time to break down this paradigm and examine its intricacies, we can see that it extends beyond the simplicity of a trend; it offers us very valuable tools for approaching our teaching and ensuring that our practice meets our mission.

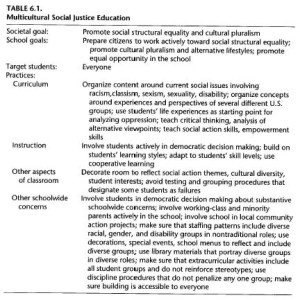

Like any trendy phrase, “social justice education” is used by too many people to mean too many different things. I tend to ascribe to the definition posited by Sleeter and Grant, in their seminal book, Making Choices for Multicultural Education: Five Approaches to Race, Class, and Gender (1988): the focus is on the students, who are in turn empowered through the curriculum to affect social change in the world. This encompasses the goals of how to question critically, how to practice democracy, and how to analyze systems of oppression, all to engage in action to actualize social justice. This implies making the curriculum relevant to the students, their experiences, and the experiences of their peers.

In their own words, Sleeter and Grant explain that social justice education “starts with the premise that equity and justice should be goals for everyone and that solidarity across differences is needed to bring about justice. The notions of equity and justice point to not just a goal of equal opportunity but also to one of equal results for diverse communities. This means that in an equitable and just society, the various institutions of society will enable diverse communities to sustain themselves, and will ensure basic human rights (including decent housing, healthcare, quality education, and work that pays a living wage) for all citizens” (2007: 197-198).

Social justice education, then, becomes more than just teaching students about the conditions of the world – it becomes “emancipatory” (to borrow a word from Freire) and empowering, giving students a toolkit to understand their condition, empathize with other oppressed peoples, and work toward collective action to change the world. Social justice education is a very strong political act.

This way of teaching often gets conflated with multicultural education, one of the approaches also discussed in Sleeter and Grant’s book. The main difference, though, is the action piece. Multicultural ed seeks to give voice to those who have typically been silenced (for example, a Native American voice during the teaching of Manifest Destiny), but this feels so distant and like a problem from the past. Social justice ed problematizes this approach in its inability to question the power structures still silencing voices today, and the need to challenge those very power structures.

In effect, social justice ed contextualizes the learning in the experience of the student, while that experience is also contextualized in the larger structures of society. Education becomes a very powerful tool for changing the world. And “these skills are not developed by telling people to think or by explaining the principles of democracy, but rather by practicing critical thought and collective social action” (197). Students learn best by a teacher who acts as facilitator and creates a lot of open space whereby the students come to knowledge themselves – because the process of learning, too, ought to be a means toward empowerment.

This way of approaching education can be very powerful – but only if we don’t let it get diluted through buzzword usage.

[/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

Reference: Sleeter, C.E. & Grant, C.A. (2007.) Making Choices for Multicultural Education: Five Approaches to Race, Class, and Gender. 5th Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]