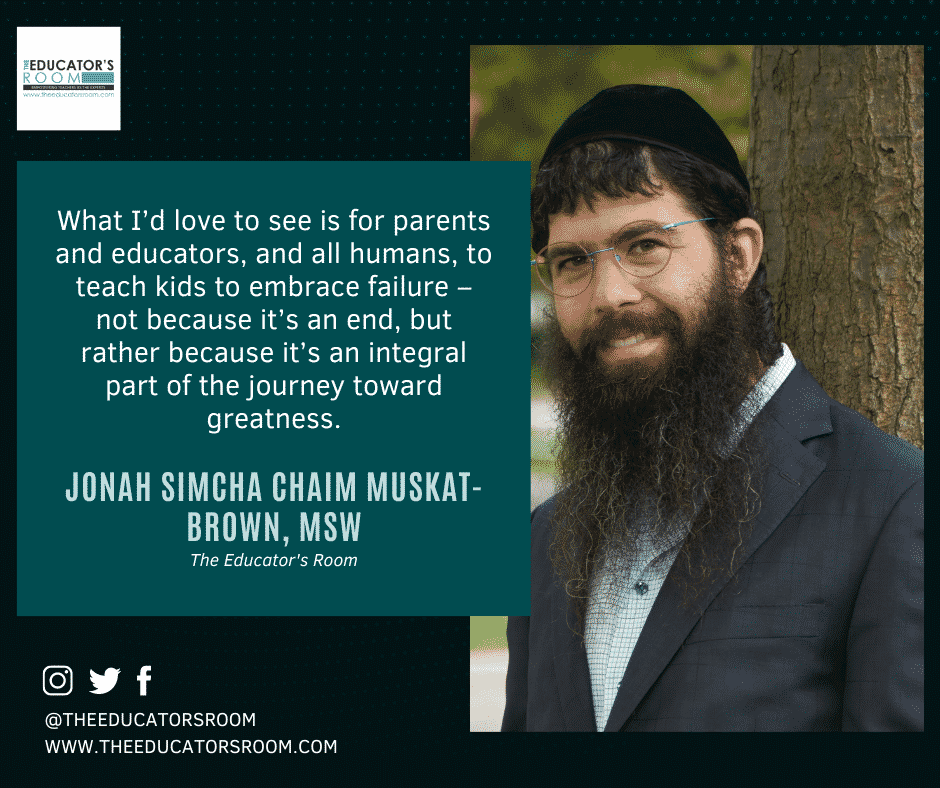

Jonah Simcha Chaim Muskat-Brown, MSW

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines the word failure in 3 ways:

- A lack of success in some effort;

- A situation or occurrence in which something does not work as it should;

- An occurrence in which someone does not do something that should be done.

A quick Google search revealed other similar definitions, but, as a social worker-turned-educator, I wonder how accurate these definitions are. As I reflect on my students’ celebrations and difficult moments over the years, and more recently during COVID-19, I wonder if we, as educators – and by extension, society at large – are helping students achieve success if we just hand out free passes and good grades in the guise of protecting self-esteem.

Are we successfully preparing our students for life beyond the classroom if we don’t teach them how to fail as much as we teach them how to excel in their academics?

To say that the past few years of living with COVID-19’s “new normal” has been difficult is an understatement. In many ways, especially for our youth, these years have been some of the hardest they’ll (hopefully) ever have to face. The medical complexities of COVID-19 have put the entire world into a global pandemic. People have lost their lives – both young and old. People have had to say goodbye to loved ones – sometimes by their side, and at other times utilizing technological video conferencing. Individual and communal mental health complexities and concerns have sky-rocketed. Schools have shut down or gone virtual. Businesses have closed or were forced to revamp. Overall, we’ve been living in a constant state of unknown. And, in many ways, this unknown is worse than the pains and challenging experiences that we’ve had – and continue having – to face.

The English language is sometimes funny in that we can have several different (or similar) words to describe a single phenomenon. Some other languages or dialects are far simpler, and looking at certain words in a language to which we’re not native can provide rich meaning and insight. We’ve since turned the page in our lives to the opening of Chapter 2022, and as I reflect on the year that was and aspire to the year that can be, I’m reminded of a word in the Hebrew language: shana (sha-nah). Like failure, this, too, has three different meanings (at least three of which I’m aware). Depending on the context, shana can mean year, old, or change/shift. I share this because I think it’s powerful. Our year (or week, or day, or set of minutes) may seem like a repetition of what we already know or an occurrence we’ve already experienced before, but it doesn’t have to be. To be human means that we can choose to shift our focus. We can’t change what we see, but we can change how we look. Mindset is everything.

Let’s get back to failure. We all have ideas of how life is supposed to happen and how we’re supposed to live out our days. We have conceptions of what’s expected and appropriate – and the opposite. And, truthfully, we do need these baseline standards if we hope to attain any sense of societal (or global) cohesiveness. But what concerns me is that we base our standards on external factors and voices. We look at others – whether those closest to us or others we’ve never yet met who live in different cities, or countries, or time zones – and we measure success (or the opposite) based on what’s happening over there.

What each of Merriam-Webster’s definitions of failure fails to do (and any other time I’m having this discussion elsewhere) is look at what’s happening over here. We fail to look within at who we are as individuals and the host of talents, skills, and challenges that make us us. When we say that failure is a lack of success in some effort, we need to ask ourselves to whom are we comparing that effort. As students, are we comparing our work to others in our classes? As children, do we compare ourselves to older (or younger) siblings? The same questions apply to teachers and parents. Why do we sell ourselves short by deciding how successful we should be before we even embark on a task or project? If we truly gave it our all, why can’t we say we achieved success even if we didn’t hit the mark we might have initially set for ourselves?

When we determine in advance what success looks like – and that can be in academia, work, athletics, arts, beauty, or whatever – we subconsciously create barriers for ourselves because we decide how something should look and not how it could turn out. We look at those around us and the popular social discourses of our time, and we settle for outcomes decided by others; we rob ourselves of the opportunity to determine our greatness.

Measuring success and failure this way makes life predictable – and in many ways, that can feel comforting. The sun rises and sets only to repeat itself the following day – or so we hope and count on. But in this reality of repetition and familiarity, there are no (or severely slim) opportunities for possibilities beyond our current awareness, no room for curiosity or creativity – just conformity. As teachers and parents, and as individuals, we need to give ourselves permission to dream, to look beyond what we know and discover (and re-discover) ourselves afresh within that process. As much as we may follow the routine patterns of bio-psycho-social development that says we’ll develop, begin a family of our own, and meaningfully contribute to society in some way(s), we need to be able to shift within this format and be the deciders of what greatness we want to attain therein. We need to allow our children and students to discover who they are beneath the many external voices of success and to let that shine.

So, am I advocating that we not care about outcomes, let our children or students make whatever choices they wish, or take a step (or many) back from our many responsibilities? Are we, truthfully, better off without a baseline of acceptability and accountability? Am I encouraging that everyone is freely given an A? No, I’m not.

When we downplay and teach the fear of failure, we discourage creativity. We sell ourselves short, and we put a cap on growth. We tell others (and ourselves) that taking risks isn’t worth their time or effort. Being creative or trying new things isn’t worth the energy it takes because failure pushes us back, not forwards – and why risk it? Essentially, we tell people that success has one direction, one model, and they either have it or don’t.

What I’d love to see is for parents and educators, and all humans, to teach kids to embrace failure – not because it’s an end, but rather because it’s an integral part of the journey toward greatness.

I want to see young people unapologetically step out of their comfort zones and embrace all that life has to offer because they know that we adults are there to support and guide them on that adventure. I want to see us creating safe spaces in which they feel brave enough to choose a path less traveled upon, knowing that we’ll be there to guide them along the way.

Jonah Simcha Chaim Muskat-Brown, MSW, is a Teacher Candidate in the Faculty of Education at York University. He has long since given up on the idea of failure.