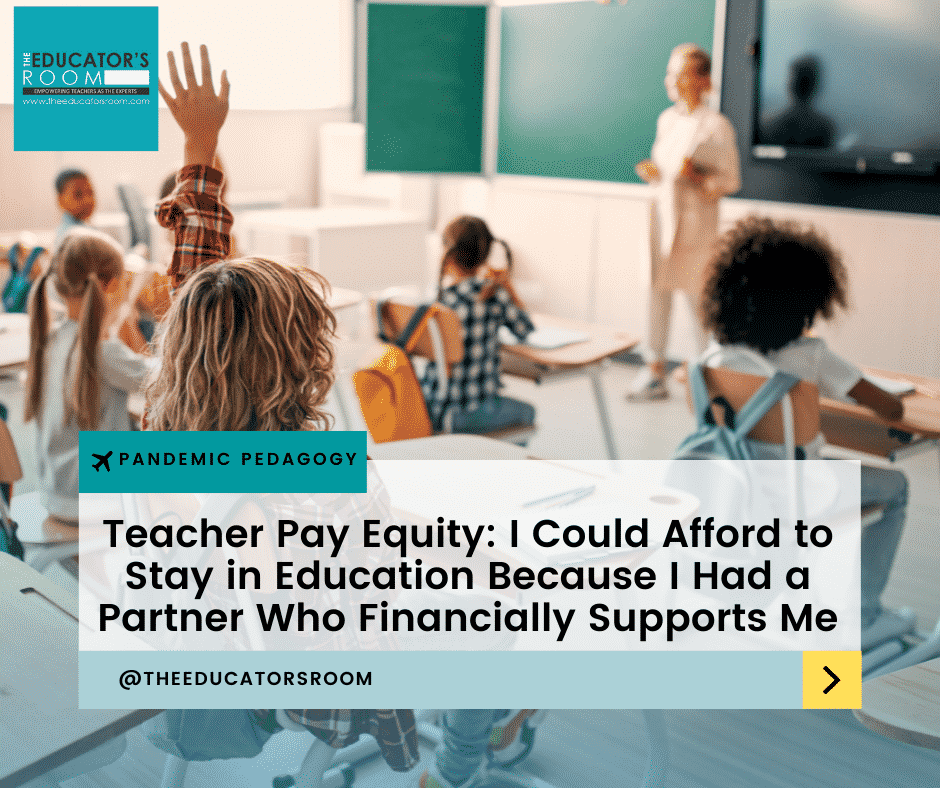

This article is an ongoing dialogue from teachers worldwide about what happens in education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sometimes I forget that I have spent my entire adulthood in a two-income household.

When I first started teaching twenty years ago at a small private school with a measly $22,000 salary, my new husband was still making more than me as a production scheduler working at an hourly rate. While we made many common 20-something financial mistakes that landed us thousands of dollars in debt, our combined income was just enough that our mistakes didn’t completely sink us. We were still able to eventually buy two cars and a small house in Indianapolis and take the childcare hit when I finally gave birth to our daughter.

After eight years of teaching and a position at a new school, I still wasn’t making more than $35,000. We had accumulated enough debt from living at our means that I couldn’t afford to not work (and I still wanted to teach). We were lucky enough to find a good in-home daycare that would still leave my paycheck in the black, but our financial situation was not great. It took another significant turn when I had to quit my job because my husband got transferred to another city; my eventual Teaching Assistant pay after I started graduate school covered a couple of days a week of daycare and one of our car payments.

It has taken a long time, but with nearly 20 years of experience, a Master’s degree in English, and multiple moves, I am probably finally making enough money that our family would be ok if we were hit with a tragic emergency. But I’m not the first to say that is not good enough for a highly educated veteran in a professional field that requires at the very least a bachelor’s degree, unpaid internship, passing multiple standardized tests, and licensing in each state the professional chooses to work.

When I compare my salary with other teachers with the same level of experience and education and consider where I live, I can state that I am fairly compensated. I don’t suffer from deep dissatisfaction in regards to my salary because I only really know how to compare my salary to those in my field.

But if I were to consider my nearly 20 years of teaching experience from high school through college, my subject area Master’s degree from a major state university, and the number of workshops and training I have attended over the years, and compare that with my peers who chose other fields instead of education, then the dissatisfaction with my salary creeps in.

Because the reality is that we are willing to pay more for something that we value, and if you look at teacher salaries across the country (average starting salary in the US is nearly $46,000, but the range really falls between $40,000 and $53,000), it is clear that we don’t really value education.

We should strive to have teachers who are the brightest and the best in their fields. That means we should want teachers who went to good universities with strong academics and challenging programs that weed out those who should not be in education. But to achieve that goal, teachers need to spend money to attend strong universities where they will be surrounded by experienced mentors and equally driven peers who are interested in more than just a degree. It means putting themselves in an educational setting where they are surrounded by field experts and given opportunities to learn from others willing to give their time to visit with students around the country to share their experiences and expertise.

And it means finding a way to pay for the tuition accrued over the four to six years that college students are doing all of that learning to become effective educators. Today, nearly half of all educators still owe an average of $58,700 on student loans, student loans they willingly accepted so that they could do a job that is essential to the very foundations of our democracy.

I went into education because I wanted to be an English teacher. I wanted to teach teenagers to love reading and writing. I wanted to make a difference.

And if I hadn’t had a spouse who made more than me and was able to financially support my efforts to work my way up the educational ladder, I might have been forced out of the field a long time ago.

The domino effect of low teacher pay can be seen in nearly every aspect of education. College students who love working with children and have the potential to be amazing educators choose to stay out of the field because the low starting pay stands in the way of their other life goals, including starting their own families, homeownership, and travel. Young teachers who want to stay in their school building (and who often fear upsetting administration) will often load up on extracurricular activities that will pay them a stipend, turning their teacher work weeks into daily grinds that last up to twelve hours or more a day, leading to faster exhaustion and burnout. Teachers of all ages who find themselves taking second jobs or looking for side hustles that they can do from home end up spending time that could be devoted to perfecting their teaching craft on making money to help ends meet. I’ve seen excellent teachers who belonged in the classroom take administrative jobs because it was the only way they could afford to stay in education and still provide for their growing families.

We are in the midst of a teacher shortage crisis in the United States, and while low pay is far from the only reason why, that reality is certainly not convincing people to stay in a job that continues to require more of us, and that was before a global pandemic made everything even more difficult.

Quality teachers are the bedrock of a strong education system. This is the case from early childhood through the university system. And low teacher pay is a problem at nearly every level and in nearly every kind of school. No, we don’t want teachers going into education for the money, but I could say the same for my family physician or dentist. We pay professionals in other fields enough money to attract them to the field and keep them there, rewarding them for their hard work and positive outcomes. We should be doing the same for education.

If quality education is the bedrock of a functioning republic and is necessary for developing the minds of every individual who will eventually enter the workforce, shouldn’t we be treating the ones responsible for preparing children and young adults for active citizenship like the essential workers that they are?