Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

I remember having my qualifications questioned, dissected and scrutinized. I remember having to pause, take a mental step back and gather my thoughts before responding to an attempt to get me to fulfill the stereotype of an “Angry Black Woman”. I remember very clearly recently advocating for my son’s education. When I made it clear I would employ all resources to continue to fight for his educational rights, my mere mention of questioning policies and procedures was seen as “combative”. I was careful not to raise my voice. I was careful not to use profanity. I was careful to be as professional as possible while stifling “Mama Bear” emotions welling up inside me begging to be released, but none of my efforts mattered.

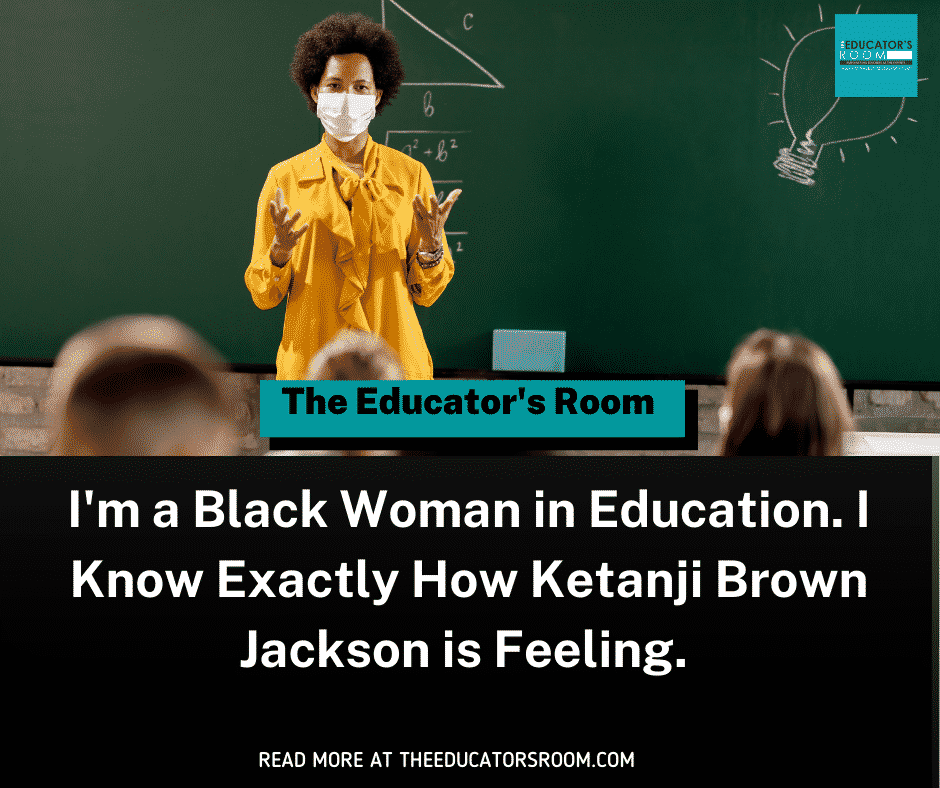

I have employed the same restraint as a Black woman in education as Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson is displaying in her Supreme Court confirmation hearings. I have experienced things as simple and seemingly harmless as colleagues looking at me to see how I will react to racism or sexism on campus, as if my reaction will somehow distract or even add to the egregious nature of whatever “ism” has taken place.

As a Black woman, a Black parent and a Black educator, I find myself triggered on so many levels while watching events like the confirmation hearing of Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Attacks on Professional Black Women

I’m not alone. The Los Angeles Times‘ Arit John spoke to Black women who saw many parallels between their experiences and Judge Jackson’s. Dr. Nadia Brown, chair of Georgetown University’s women and gender studies program told John, “This is just a master class in how Black women have to be patient, have to be fully composed in responding to things that are meant for destruction. These are the kinds of attacks that Black women get in their professional roles.”

I remember meeting parents in person for the first time at Back to School Night decades ago. One of the first things said was, “Oh, you sound different on the phone”. I knew this was code that meant they did not know that I was Black. At the same Back to School Night, I gave my introduction and saw eyebrows raise when I shared that I held a Master of Arts’ degree, and that I taught part time at a college.

“Why teach high school then?” one parent asked. I knew this was another coded message meaning that I didn’t cut it as a full-time professor. What they did not know at that time was that I had never even applied for said position. I was recruited based on my experience and expertise. I remember continually advocating for myself, my programs, my clubs and my students and having staff say that I often come off as “scary” or “intimidating”. My passion and perseverance are often perceived as arrogance. But, advocating for one’s self and others with confidence should be seen as a positive quality, no matter one’s racial or gender identity.

“Can I help you?”

The same LA Times article quotes Alexis Hoag, an assistant professor at Brooklyn Law School. “As a Black woman who also served as a federal public defender, it’s hard to watch because I can’t divorce all these aspects of her identity from the way she’s being treated.”

I remember being questioned in the staff parking lot of my college with a seemingly innocent “Can I help you?” as I parked my car. I looked at the “colleague” then back at the very visible “Staff” placard hanging from my rear-view mirror. I smiled and said what was becoming a yearly explanation. “I’m here for the faculty flex meetings”. There was not even the subtle crimson evidence of embarrassment. The kind that usually comes over another’s face when they realize they have made a discriminatory comment. “Oh, ok.” I was left standing there to process, once again, and wondering how many times I would have to have this experience. I, too, could not divorce my identities from the way I was being treated.

The LA Times article also quotes a tweet from Sherrilyn Ifill, a civil rights lawyer and the former head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “The sigh. The pause. The double blink. The angle of the head. Volumes spoken before giving the answer. We understand.”

I understand all too well. As a Black woman in education I have had to employ this exact series of nonverbal reactions before a response more times than I can count. The sigh equates to my exasperation. The pause is a sign of wisdom learned from countless similar episodes. The double blink sadly sometimes stifles tears of anger raging inside me. The angle of the head is my version of a “side eye” at the audacity of the question, accusation or even blatant attack on my identity. These questions and comments attack me as a parent, my identity as a teacher, or my identity as someone with the same, if not higher, intellectual capacity as others. I, too, understand.

All Educators Should Watch the Confirmation Hearings Closely

A quote that went viral this week encapsulated Judge Jackson and every Black woman’s experience well:

“For overqualified women who have to remain calm, friendly, knowledgeable and professional in front of underqualified men…Lord, in Your mercy, hear our prayer”

As Black women in education, be it as a paraprofessional, a counselor, a teacher or administrator, we are looked at with a critical lens our non-Black colleagues may never experience. I would encourage all educators who call themselves anti-racist, culturally affirming change agents to watch these hearings with a close eye. While watching, think about your colleagues who are Black women. Think about how and why we can relate so much to this hearing as Black women, and why it is so hard for many of us to watch.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.