We got the kids back. So why is it still so hard to reach them?

Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

Like many educators, I was excited when we managed to reopen our little Washington DC charter school last August. As middle school principal, I’d led enough student meetings on Zoom the previous year that I’d come to dread those black boxes, the children’s voices deteriorating into robot talk, the view of bedroom ceilings. Eager to be back in front of real, three-dimensional students, I took on the task of subbing for our middle school science class, left open by a late vacancy.

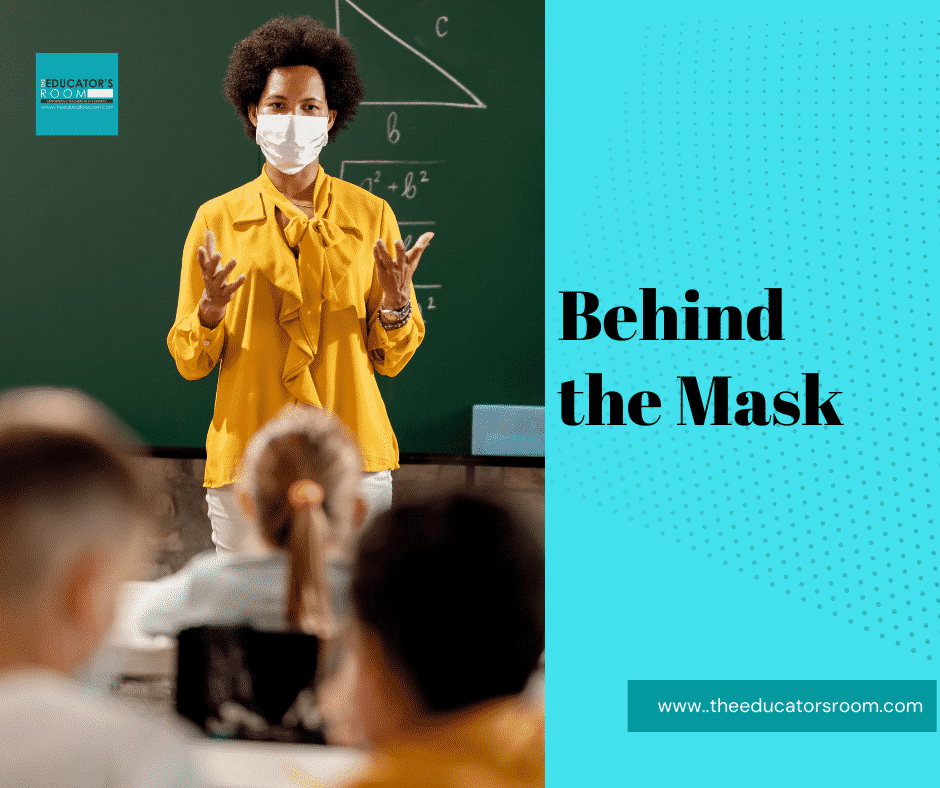

But after only a few weeks the initial burst of joy ceded to an exhaustion and sense of incompetence I had not experienced since my first year of teaching, twenty years before. Suddenly, teaching felt like wading through mud. My equally exhausted colleagues and I theorized that the students were learning how to be in school again, that we ourselves just didn’t have our stamina back, that the pandemic had everyone distracted. But it was a college professor friend, who teaches giant lecture hall classes, who helped identify what was bogging me down the most: The masks.

“I’m up there talking and I look out,” my friend explained, “but I can’t get a read on the room. I can see their eyes, but I need the whole face.”

Like me, my friend is supportive of mask-wearing in classrooms. His comment was not an attempt to undercut public health science but a reflection on the psychological difficulty of communicating with another human being whose face is half-concealed. You don’t have to read the peer-reviewed studies on non-verbal communication to grasp the important role played by our faces. Think of your mother’s tight-lipped disapproval, or Harrison Ford’s signature smirk. Our faces reveal tons of information essential to connecting, responding, and building relationships. It’s why we insist on having those thorny conversations “face-to-face”; why Georg Lichtenberg declared the human face “the most entertaining surface on earth.”

Back to my science classroom. Under any conditions, 12-year-olds can be tricky to read. Usually they’re thinking about something very different ( their latest crush, their shoes, Takis) than what we teachers want them to think about (fractions, when to use “its” vs “it’s”, why to be respectful). They are also experienced enough with school that they can track a lesson with minimal attention, and when asked to write or speak about what’s going on in class, they can typically garner a somewhat accurate response.

I find them less savvy with their faces, however, than with their words. Back in the maskless days, whenever I introduced a new assignment, I took stock of the facial expressions as I spoke: slack-jawed shock, frowns of frustration, or–if I got it right–eager smiles. In an instant, I knew if the assignment would be a success or a fail. I could make adjustments as I taught.

Even more important is having access to my student’s faces when I’m trying to build rapport, especially with those who have little reason to trust adults. I’ve spent weeks trying to get a particular student to smile–corny jokes, pranks, offkey singing of pop songs–because there’s tremendous power in catching a kid smiling, usually in spite of herself. A bridge magically appears between two distant islands, connecting teacher to student in a way that makes learning possible. Winning a student’s smile is certainly not the goal of a learning relationship, but it is often the beginning, and a hard-won beginning at that.

My college professor friend helped me realize that a large part of my exhaustion was due to the fact that I no longer had access to this critical source of information–call it “data,” if you’d like. It was as if the gas gauge on my car’s dashboard had vanished: gathering key information that I once checked without a second thought had become a laborious, stressful process.

To compound the issue, masked teaching not only robs teachers of key data, but also of one our best resources: our faces. My first year of teaching, a colleague shared with me the old axiom, “Don’t let them see you smile till Thanksgiving.” I ignored him and built a pretty successful teaching career on communicating expressively with my students through a variety of smiles, smirks, grimaces, winces and frowns. You’d be surprised at the disasters I have averted with a tightening of the lips (“Let go of her ponytail, Angelo”) or the tiniest of grins (“It’s not really a pop quiz, friends”). Like many teachers, my face became one of my most effective pedagogical tools–but that too, was gone.

The realization helped me understand why teaching that science class was so exhausting. This year, of all years, was the year I most needed to be communicating with my students deeply and expressively. We needed to reach out of our quarantine shells to share our fears and hopes, and reassure each other and commiserate in our collective grief. This was the year we most needed to be building relationships. And relationships require so much more than the exchange of lessons and content.

I suspect that my experience is not mine alone, that much of the burnout reported by teachers across the nation has to do with this obstacle to human connection. As the pandemic subsides, and masks are no longer needed, I am hopeful that the rebuilding of these critical school relationships begins in earnest–starting, as so many relationships do, by simply sharing a smile.

A graduate of Brown University (BA) and the University of New Mexico (MA and Ed.S), Seth Biderman is an experienced educator and school administrator. He has worked in public and independent schools in New York City; Cali, Colombia; Washington, DC; and Santa Fe, NM. He has also founded and directed out-of-school mentorship programs to connect young people with areas of personal passion. He is currently principal of the 7th and 8th grades and Arts, Languages and Movement program at the Inspired Teaching Demonstration School in DC.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.