34,000 Feet – Somewhere Over the Atlantic

I was utterly crushed. There is absolutely no other word to describe it. On the eve of my last day of a magical family holiday, I got the bad news. For the second year in a row my AP scores were disappointing…VERY disappointing.

In the wake of last year’s disappointment, I did what I always do when encountering lackluster results – I enthusiastically embraced the challenge. The proper response to failure is not to wallow or caterwaul about. Innovate. Improve. Examine one’s efforts with brutal honesty. This formula had always worked in 14 years of teaching Advanced Placement students. I had years of success to validate it. One year of disappointment typically yielded three or four years of decent success before an off year would once again rear its defiant head, catalyzing tweaks, reforms, and adjustments anew.

This cycle of success and failure is sewn into the very fabric of a teaching odyssey. There is no escaping it, not even for the finest teachers alive.

In the past, I responded by creating a YouTube channel, I started a Twitter account, I altered my reading assignments and homework expectations. I started lunchtime reviews, wrote a grant for AP review books, and the list could go on and on. This year I made the decision to focus solely on one AP exam – AP government – instead of two. For 12 years I prepared my seniors to take the AP Macroeconomics exam as well. But to remedy last year’s failures I wanted more time to review and teach the course content. I was tired of being rushed all the time. I radically changed the course calendar, offered the most thorough review process of my career, and gave more practice exams. I had high hopes that once again my faith in the power of innovation would be vindicated. The students felt confident they had performed well.

In the past, I responded by creating a YouTube channel, I started a Twitter account, I altered my reading assignments and homework expectations. I started lunchtime reviews, wrote a grant for AP review books, and the list could go on and on. This year I made the decision to focus solely on one AP exam – AP government – instead of two. For 12 years I prepared my seniors to take the AP Macroeconomics exam as well. But to remedy last year’s failures I wanted more time to review and teach the course content. I was tired of being rushed all the time. I radically changed the course calendar, offered the most thorough review process of my career, and gave more practice exams. I had high hopes that once again my faith in the power of innovation would be vindicated. The students felt confident they had performed well.

They were wrong. VERY wrong.

[bctt tweet=”This cycle of success and failure is sewn into the very fabric of a teaching odyssey.” username=”EducatorsRoom”]

There is nothing worse than being on vacation and riddled with disappointment, confusion, and a titanic tonnage of professional self-loathing. My students counted on me to get them to the finish line. But I didn’t, at least not for most them. And worst of all, I failed in a year in which I had doubled my efforts. There is no elixir, no panacea, no secret sauce in the teaching process. Just a steady but committed attempt to get marginally better every year.

But I’m not. And here is my confession: I’m getting worse, or so it feels. I passionately care  about my students, my craft, and about the subject I teach. If ever the world wanted to make the point that “feelings” don’t translate into results, this is it because I certainly felt like I had had a good year in the classroom with my students. Instead, I now feel like the weight watcher who diets, exercises prodigiously, and then steps on the scale only to see weight gain.

about my students, my craft, and about the subject I teach. If ever the world wanted to make the point that “feelings” don’t translate into results, this is it because I certainly felt like I had had a good year in the classroom with my students. Instead, I now feel like the weight watcher who diets, exercises prodigiously, and then steps on the scale only to see weight gain.

“What,” I want to scream, “is going on here!?!?”

The obvious answer is I am not getting any better. I’m sliding backwards in my teaching. This happens all the time to teachers who reach the third-decade plateau of a teaching career. Usually this decline, however, is a willful decision to ease up on the throttle of classroom excellence. Enthusiasm dries up. Cynicism manifests itself in a teaching persona. Vigor and dynamism began to wane. It happens. It happens a lot. And it is nothing to be proud of in our profession when it occurs.

But here is the rub: I’m absolutely, positively trying my best. I had an enjoyable and productive year with my students. I hope most of them would say the same.

The next morning after I learned of my disappointing scores, my father, oldest daughter, and I embarked on a day trip to Oxford. It was our last day of a one-week England summer vacation and I had always wanted to visit the most famous university in the world.

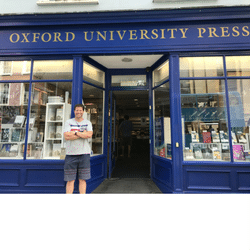

It was utterly, ineffably, magnificent, splendorous beyond words. Around every corner and down every street was something awe-inspiring. My father and daughter got tired, I’m sure, of me constantly exclaiming, “WOW!” The entire city exudes a cerebral energy, unlike any place I have encountered in my travels. We toured the oldest college at Oxford, Balliol (1263), where Adam Smith attended, gazed at the beauty of the Ivy-sprawled Lincoln College which was founded in 1427, and walked to top of the highest tower in town from the Norman era. We indulged our inner-bibliophile by sopping up titles at the original Oxford University Press book shop which opened in 1872. It was magical and glorious and utterly enthralling. It was, in short, one of the best days of my life.

This was, after all, the college of Shelly, Newton, Einstein, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hobbes, C.S. Lewis and just about every other world leader of the 20th century, it seemed. On the train ride back to London afterward I reflected on the AP scores, and for the first time in my career, I didn’t know how to proceed.

It occurred to me that while my name does not belong in an Oxonian pantheon with any of the men I named, I still felt as I walked the streets the delicious enjoy of being a (somewhat) intelligent and sentient human being capable of a meaningful understanding of life and much that it has to offer. I know I am no scientist, philosopher, or scholar, and yet I’m bright enough to sympathize with Aristotle’s sentiment that the most sublime human pleasure of all is the pleasure of understanding. To yearn for knowledge, to transcend one’s primordial ignorance, to feel the glory of exquisite insight and wisdom, is to break open the existential egg of life’s richest possibilities. To learn, to read, to breathe deeply, feel passionately, think deliberately, is to drink the sweetest nectar the world has to offer. My Oxford walk reminded me of this.

As a young man, I tasted this nectar because of the extraordinary teachers who taught me. I became a teacher so that my students could experience youthful palpitations of inspiration similar to what I felt as a young person, or perhaps even the electrification of what I felt walking the streets of Oxford. My specific door to this magic was opened by a profound interest in politics, history, philosophy, and economics. But there are many doors to the delight I experienced at Oxford.

The reason my heart is heavy, the reason I want to cry out, the reason I feel like a colossal failure… is because I used to believe my classroom was one of these doors. I became a civics teacher to enchant and edify, uplift and inspire with the story of the greatest civilization to ever to exist, the United States of America. Somewhere along the way, however, this ambition devolved, I exchanged the Academy for the College Board, Gettysburg for Princeton, New Jersey. And now that my ability to get my students to the AP exam finish line has suddenly vanished, I’m not sure what I have achieved.

And so, I’ve created my own form of a teaching purgatory. I’m not sure how to get out. It’s early July which means it’s the season for teacher reflection. Each school year affords a teacher an occasion for both remedy and redemption, sentimental though this may sound.

This opportunity is the greatest gift our profession affords us—that success may be delivered from the crucible of failure. Let’s hope it happens again.