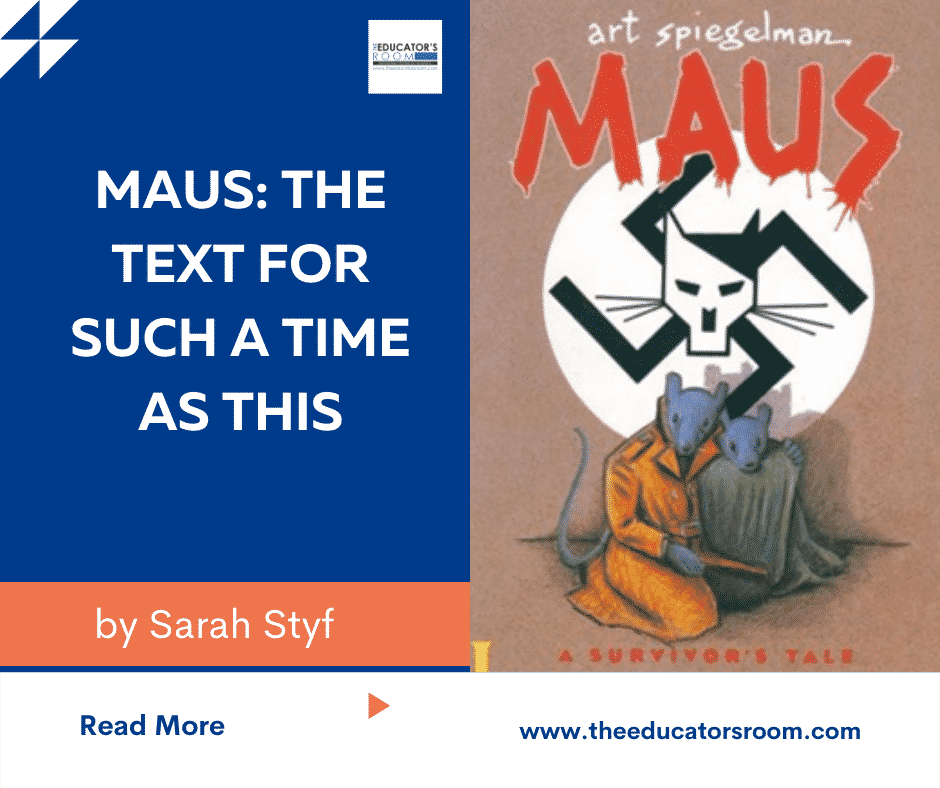

I read Maus for the first time nearly 20 years ago. It was required reading for my adolescent literature class, one of the many English classes I took for my undergraduate education program. My professor hoped that we would value using a graphic novel in the English classroom. So I flew through Volume 1 and 2, falling in love with Art Spiegelman’s haunting drawings and engaging story. I saw the value of using words and pictures to teach my future students literature for the first time.

It also gave me one more valuable text that I could use during a Holocaust literature unit.

Over the years, I have found several ways to bring the memoir into my classroom, always wishing I had access to the full text so that I could use it as a compliment to Elie Wiesel’s Night. Every time I have had my students read portions of Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning text, they’ve commented on the shockingly powerful way images of mice and cats have helped them better visualize what even Wiesel’s haunting prose could not: the attempted extermination of an entire people.

My love for the text has never wavered, and neither has my conviction that it is a book that should find its way into my student’s hands.

For nearly 30 years, the explosion of young adult literature has also meant that there has not been a shortage of Holocaust literature available to students from elementary through high school. My first exposure to the genre was when I was a sixth-grader and read Lois Lowry’s then newly released Number the Stars, which I have now read with my daughter. Schindler’s List came out during my freshman year of high school, and I observed from the outside as the juniors in my high school got permission from their parents to attend a special screening of the film at our town’s primary movie theater. I watched it two years later in my AP US History class after we took the AP exam; again, our parents signed over permission to watch an R-rated film that was full of violence, nudity, and the horrific realities of the first systematically planned and executed genocide of the 20th century.

And to be perfectly clear, it was not the first genocide of the 20th century, and it would not be the last. But it would be the most carefully planned and documented genocide in modern history, and remembrance of the death of six million Jews and over six million others – including the mentally and physically disabled, Poles, Russian POWs, homosexuals, gypsies, and political prisoners – has become the basis of the rallying cry “Never Forget.”

But between the time I read Number the Stars and watched Schindler’s List in the 1990s, the war in Bosnia had led to the establishment of concentration camps and the rape and slaughter of thousands of Bosnian Muslims and Croatians, and Rwandan Hutus killed nearly one million Tutsis in a matter of months. Shortly after I started teaching nearly 20 years ago, war broke out in Sudan, and I found myself using Darfur as a modern example of genocide when my students read Night. In recent years, my students have researched the Rohingya in Myanmar and the Uyghurs in China.

Genocide has always been there, sitting on the periphery where most American students cannot see it. While children their age are losing family members and fighting for their lives, they sit at a relatively safe distance. As a parent and a teacher, I am thankful that they are safe. I am grateful that they are not witnessing the worst of humanity. I am grateful that our country is not destroyed by violent civil war.

But that doesn’t mean that our children should be protected from the experiences of others. That doesn’t mean that I don’t want my children to read The Diary of Anne Frank and to visit the Holocaust Museum on their eighth-grade class trip.

And that especially doesn’t mean that I want my children to have a book like Maus taken out of their middle school classroom because it is too “real” for them to handle.

As a parent, I empathize with the desire to protect children from reading material that is not age-appropriate. I’m not going to give my 10-year-old who loves war stories The Things They Carried. I’m not going to sit down with my 12-year-old who devoured the original The Diary of Anne Frank to watch Schindler’s List. But I have to wonder at the motivation for doing so with a book like Maus.

The reported nudity is microscopic, non-sexual, and not intended to arouse the interests of adolescent boys. (In fact, most people who have read the book don’t even remember it, myself included.) Moreover, the language is milder than most of the media that middle school children are exposed to nearly all day on their personal devices, video game consoles, or family computers and television. The same could be said for the cartoon drawings of violence, including, yes, the hanging of Jewish prisoners in a concentration camp.

So why would a teacher want to use it? It shows the gradual loss of rights by all citizens caught in the web of a fascist government. It effectively highlights the events that led to war and then genocide. Third, it shows the long-lasting effects of oppression even after the actual oppression has ended.

In Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451, another book frequently taught to students before they graduate from high school, the character Faber tells the fireman Montag, “So how do you see why books are hated and feared? They show the pores in the face of life. The comfortable people want only wax moon faces, poreless, hairless, expressionless.”

Teachers spend hours, weeks, and even months researching the best options for teaching their students. They read multiple books, go to workshops, and seek the advice of other teachers who have taught the same material. Then, as they get to know their students, they look for both engaging and hold educational value. They look for books that show “the pores in the face of life” because to make something terrible seem less terrible than it was is to allow our students to believe a lie. As teachers, we want to raise empathetic and critical thinkers citizens. And at a time when literacy rates are dropping, and teachers are struggling to get students to read anything at all, the last thing we should be doing is taking engaging literature out of a classroom where it can be read and discussed and studied but whole groups of students.

Suppose parents and community members are really concerned about what children are being taught. In that case, they should instead be ensuring that teachers have time and access to workshops and training that prepare them to use best practices with their students and teach them to use a variety of texts to teach students critical thinking. Parents should read the books their children are reading in class and them. Instead of panicking because they saw a single word or image, they should read the whole work, gaining a complete understanding of the context and purpose of the piece and taking the time to think critically. They should discuss the text with their kids, and if they have concerns about content, they should see that as an opportunity to discuss it with their children before raising those concerns with the teacher. This is the kind of partnership that literature teachers would love to promote, one that encourages literacy, understanding, and community.

Maus is about so much more than the Holocaust. It is about the redemptive nature of storytelling. It’s about the healing of a parent/child relationship damaged by a father’s unresolved trauma. And it is about the resilience of the human spirit.

Maybe everyone should just sit down and read it.

Awesome article, this from a child of survivors. Thank you for giving voice to our outrage over Maus’ removal.

Excellent piece Sarah! I was in AP English in high school decades ago, and read many challenging and thought provoking books. I started college as an English major, and even though I eventually changed majors, I continued to take courses that interested me. It was decades before Maus, I think. I’ve wondered what the fuss was about. It’s probably time to read it…