Brian Francis Smith is an educator, author, podcaster, husband, and father of two middle school-aged daughters. He is in his 19th year of teaching English at Cheltenham High School, a public school outside of Philadelphia. Brian is the author of two novels and has taught creative writing at the Philadelphia Writers’ Conference. He currently teaches 12th grade Project Based Learning, a program he helped pilot four years ago. Brian is also a 12th-grade internship advisor and a guidance counselor for gifted students. When not teaching, he can be found hiking the rocky trails of Pennsylvania with his family and dog Lucy or enjoying a bad horror movie. Follow me on Twitter @BrianFrancis

Brian Francis Smith is an educator, author, podcaster, husband, and father of two middle school-aged daughters. He is in his 19th year of teaching English at Cheltenham High School, a public school outside of Philadelphia. Brian is the author of two novels and has taught creative writing at the Philadelphia Writers’ Conference. He currently teaches 12th grade Project Based Learning, a program he helped pilot four years ago. Brian is also a 12th-grade internship advisor and a guidance counselor for gifted students. When not teaching, he can be found hiking the rocky trails of Pennsylvania with his family and dog Lucy or enjoying a bad horror movie. Follow me on Twitter @BrianFrancis

When I joined Twitter a few years ago it was like I had finally found my tribe. As a Project Based Learning teacher, I was constantly seeking new ways to improve my craft and inspire my students. Twitter connected me with like-minded, positive people from all walks of life. While we were not all educators, we did seemingly share a common worldview: a philosophy rooted in hard work, self-reliance, and a “glass-half-full” attitude. I soon discovered that this shared philosophy had a name: Stoicism. And it’s this philosophy that now guides my teaching and my life.

[bctt tweet=”Rather, Stoics attempt to channel the bulk of their emotions into things they can directly influence or change.” username=””]

First of all, Stoicism doesn’t mean to act cold or indifferent toward the world. Rather, Stoics attempt to channel the bulk of their emotions into things they can directly influence or change. Admittedly, recognizing the things you can influence or change is easier said than done, but once you view your classroom through this lens your students will benefit greatly.

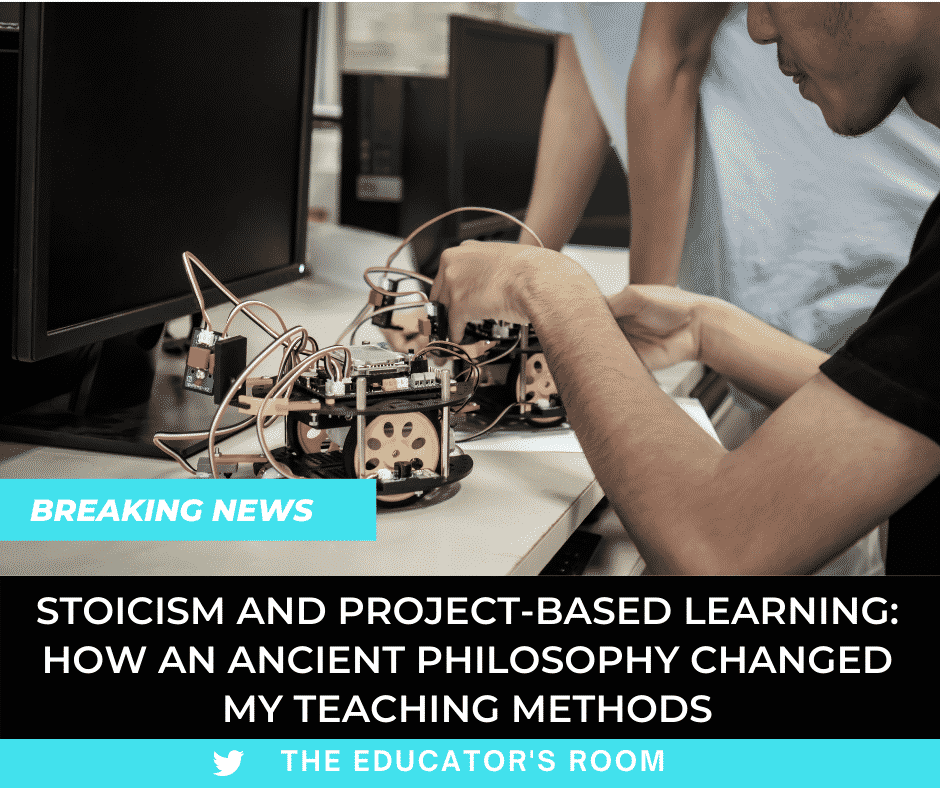

When I develop projects with my students through the lens of Stoicism I frequently consider those projects that change or influence the world around us: a new bookshelf in our high school’s lobby; a freshly painted mural in the hallway; environmentally-friendly bat houses in the courtyard. Stoicism encourages controlling what you pay attention to and paying attention to the things you can control.

But what does Stoicism mean in my day-to-day classroom? How does this philosophy influence our daily discussions, routines, and behaviors? During the day I try to abide by two overarching Stoic tenets:

Amor fati (Latin: “Love your fate”) The mental health needs of our students are greater now than perhaps at any time in our history. Stoics believe that you can certainly change your fate, but you should also consider obstacles and challenges as opportunities to shine and show your character. Project-Based Learning presents plenty of daily challenges for my students, from developing a project plan to organizing students into groups. At any point in this process, students may grow frustrated, fatigued, and overwhelmed. I’ve noticed that those students who truly embrace the “love your fate” ethos, welcome the challenges, and start to actually look forward to the difficult moments. Ryan Holiday’s wonderful book on Stoicism, The Obstacle is the Way, suggests that we shouldn’t try to avoid struggle, but rather, we should purposefully seek it. In other words, the way to become a better person is to do hard things.

Memento mori (Latin: “Remember Death”) While I never talk about death directly, I do emphasize to my students that life is fleeting, and question if playing a video game all night or binging the latest Netflix series is the best way to spend their precious time on Earth? When I tell personal stories in class, I frequently discuss times in which I pushed myself out of my comfort zone. My students were fascinated by my story of a 20-mile solo overnight backpacking trip I did on the Appalachian Trail last summer. They asked, weren’t you afraid of getting attacked by wild animals? I said, in truth, I was. But I was more afraid of dying in old age having never done this thing that has lived in my mind for years. I encourage my students to live their lives the same way: sensible, but with the ever-present knowledge that life is finite.

Don’t waste time!

Stoics believe that the “highest good” one can achieve is virtue. The acquisition of virtue means that your life is happy and free. But how do Stoics define virtue? And how does virtue connect to Project-Based Learning?

Stoics defined virtue as:

- Wisdom

- Justice

- Temperance (or Moderation)

- Courage

I find the Stoic’s definition of virtue wonderfully succinct and practical. I often think of these four concepts when I develop projects for my PBL class. I try to create experiences that highlight one or more of these virtues. Consider these potential projects through the lens of virtue:

Wisdom: a project in which my 12th-grade students teach our 9th-grade students a lesson about high school life.

Justice: organizing a social justice movement in our community demanding fair policing practices.

Temperance: students serving as sponsors to Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous members.

Courage: students creating a podcast discussing their hopes and fears during the Covid-19 pandemic, and analyzing their truncated final year of high school.

I’m currently doing that last project now, and so far, I’m pleased with the results. But I’m not always pleased with the results of my projects. And this brings up another important Stoic belief: you’re not special.

Admittedly, this is a shocking thing to say in our modern age. And each and every one of my students certainly have a story to share and a unique set of gifts and talents to bestow upon the world. And yet, in the past decade, education has moved from praising results to prioritizing feelings. I first witnessed this concept on the soccer field as the father of two-grade school-aged soccer-playing daughters. My daughters’ soccer league didn’t keep score. Yes, there were goals. But no scorekeeper. No numbers. This decision was made by the league as a means to shield players from the “harsh results” of competition. But here’s the thing…and here’s why it didn’t work: the kids kept score in their heads.

How does this relate to Project-Based Learning?

As an education system, we universally normalized this “feelings-first” approach to our students. The results being they often crumble when the prototype of their project encounters feedback or criticism. The unstated belief is: “my project is great because I made it.” Stoics dwell in a level of absolute realism. Things are of good quality or of poor quality because of how they present themselves and function. The emotions of the craftsperson never factor into the overall assessment of the work.

This is a topic that I have debated with both colleagues and parents. Ultimately, I think the final product is the most important assessment in Project-Based Learning. And if your final product does not meet a certain standard, it might not merit display.

Some would argue that Stoicism is a cold philosophy. And in this regard, perhaps it is. But the real world only rewards products that work; why should schools use a different standard? I take into account the age of my students and their available resources, but I still attempt to hold my Seniors to the same level of competence that the real world will expect from them in a few short months.

And maybe that’s the entire point of this article. Both Stociam and Project-Based Learning meet the world where it is. Neither creates a false universe or a skewed scale of assessment. If it works, it works. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t. Stoics believe that one should live in accordance with the laws of nature. As a classroom teacher, I believe that students benefit the most when living under these same laws.

Stoicism is both a philosophy and a call to action. As a Project Based Learning teacher I can think of cool projects all day long. But without providing my students with a philosophical framework for “why” we’re doing these projects, the outcomes would not be as joyful, as educational, nor as profound.

Final thoughts. I have tattoos. A lot of tattoos. My entire left arm is covered with black and grey ink work from varying Japanese and American styles. I also have tattoos that are odes to Stoicism. My right pectoral boasts the words Amor Fati (“Love your fate.”) I look at this mantra every morning as I emerge from the shower and brush my teeth. I realize that “loving my fate” is difficult on a day-to-day level. Perhaps my car broke down yesterday or I have a sudden toothache. Like any mental or physical exercise, it’s hard to “stay in the zone” permanently. I look at my Amor fati tattoo as a reminder and guidepost. I try to remember the things I’m grateful for: I’m awake. It’s morning.

My other Stoicism tattoo is located on my left rib cage, an area I don’t recommend getting tattooed if you’re wary of pain. It says Memento mori (“Remember death.”) I’m glad it’s located on my rib cage because I don’t want to see it that much. I don’t want to remember death too much.

I’ve always loved tattoos. I love the artwork, the style, and the cultural traditions. It wasn’t until my early forties that I was comfortable enough to get an arm sleeve tattoo. Why did I do it? Memento mori. We are here. And then we are gone. We are alive. And then we are not. Do the thing you want to do posthaste because your days are numbered and tomorrow is never certain.

Your classroom should function in this same way. How lucky are you to be alive? To talk to these kids? To give them the keys to the next world?

Be grateful. Be honest. Be good.

Very interesting, a beautiful simplicity.