Happy 86th Birthday to Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Justice Ginsburg stands at the intersection of American culture because of the power of her journey, the enormity of her achievements, and the undeniably quintessential American character she exudes.

However, pop culture often rides the fast lane towards trivialization.

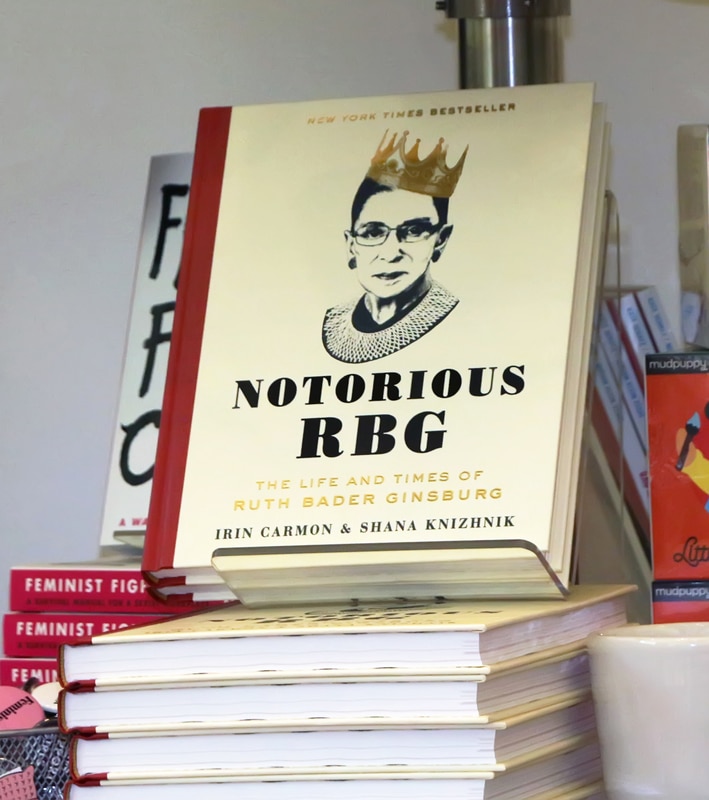

She has become, of course, a cause célèbre for news junkies and politicos whose politics are decidedly leftward leaning. Accordingly, she is the subject of adoring Hollywood films (“On the Basis of Sex”), complimentary Netflix documentaries (“R.B.G.”), SNL raps, and numerous modern biographies by esteemed academics. Stephen Colbert features her workout routine on his late-night show, there are RBG bobbleheads, t-shirts, and merchandise one would almost never associate with a supreme court justice.

The state of her health is a border-line obsession among court watchers and the journalistic commentariat who, for the most part, cannot hide their palpable sense of terror that her health may decline and President Trump will be tasked with replacing the Supreme Court’s most iconic liberal jurist.

Indeed, to study the life and career of Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a travelogue insalubrious living. For young people standing on the abyss of adult life, trying to make their way in an era of acerbic discourse, caustic online interactions, and contradictory advice about what to value and how to live, Ginsburg’s life offers a rare glimpse of what it looks like for a human being to have a titanic and historic impact on society while radiating personal qualities that place these achievements in their proper place in life’s hierarchy of goods. Indeed, when people use the phrase “having it all,” there is nobody better to study than Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

As Libby Hill of the L.A. Times observes, “. . . it feels as though by lionizing Ginsburg, we miss the most beautiful thing about her. She faces the same challenges, the same workouts, the same frustrations as anyone, yet still manages to do good things. You can live like Ruth Bader Ginsburg. You just have to stop rapping about her long enough to go out and do good.”

[bctt tweet=”There is a place for elegant and thoughtful patriotism. ” username=””]

With this in mind, there are three essential truths young people should take from the life of Ruth Bader Ginsburg:

There is a place for elegant and thoughtful patriotism.

In an era in which the art of coalition-building or “appealing to the better angels of our nature” is a lost political art form, the tone, constancy and quality of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s contribution to the American creed is a form of patriotism that is quickly—and sadly—becoming passé. After all, she is not shrill. She is not loud. She does not glory in oratorical invectives nor does she take delight in legalistic bravado in her written opinions.

In fact, in 2019 it is off-putting to discover (or remember) that women’s groups were once skeptical of Ruth Ginsburg when Bill Clinton was given the opportunity to name a Supreme Court justice in 1993. She did not particularly agree with the legal reasoning in Roe. In a speech, she famously observed, “Roe v. Wade sparked public opposition and academic criticism, in part, I believe, because the court ventured too far in the change it ordered and presented an incomplete justification for its actions.” Furthermore, when asked by the ACLU to litigate a defense of Roe, she declined the opportunity.

When Bill Clinton asked the famed senator of New York, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, to suggest a woman for the court appointment he said “Ginsburg” to which Clinton curtly replied, “the women are against her.”

Eventually, the tide turned.

She is consistently civil. But more than that, her patriotism is grounded in a universalistic faith in American political values—that America is at its best when it extends its creed, its Constitution, and its opportunities in an equitable fashion to all of its citizens. Genuine patriotism isn’t blind fidelity to country and kin—it’s a tempered but passionate commitment to ensuring that a nation’s highest ideals are neither betrayed nor bastardized by bigotry or provincial prejudice.

In her time before ascending to a federal and then Supreme Court judgeship, she volunteered for and eventually headed the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project. In time, she eventually argued a total of six cases before the Supreme Court. In four of the six cases, her only client was a man. She brilliantly chose cases that often discriminated against men in order to make a broader—and more quintessentially American argument—that “gender lines in the law are bad for everyone: bad for women, bad for men, and bad for children.”

In 2019, such a sentiment is anything but radical. In fact, it is even a little bit prosaic and banal. But there is a word for this: progress. Americans so thoroughly accept the world-view of their time—its assumptions, its values, and its posture towards the future—that we often forget there is nothing natural about the state of gender progress.

It was a fight, and no one was a better prizefighter than Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As Jill Lepore wryly noted, “Thurgood Marshall never had to battle African-Americans opposed to the very notion of equality under the law; Ginsburg, by contrast, faced a phalanx of conservative women . . .”

Family Transcends All

On June 14, 1993, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Bill Clinton. In her comments during the nomination ceremony, Ginsburg referenced her family, humorously relating this story about her daughter, Jane.

“In her [Jane’s] high school yearbook on her graduation in 1973, the listing for Jane Ginsburg under ‘ambition’ was ‘to see her mother appointed to the Supreme Court.’ The next line read, ‘If necessary, Jane will appoint her.’ Jane is so pleased, Mr. President, that you did it instead, and her brother, James, is, too.”

In January of 2015, The Atlantic published an article by one of Ginsburg’s law clerks, Ryan Park, in which he wrote a moving article about “What Ruth Bader Ginsburg Taught Me About Being a Stay-at-Home Dad.” It is a powerful article about the difficulties of putting family ideals into practice.

He was inspired by Ginsburg, who he refers to in the article as “The Boss.” Early in her marriage, her husband, Marty Ginsburg, was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Her response to her husband’s illness was almost superhuman in scope—not only did she care for both he and their young baby, but she also kept up with all of his classes and assisted him in writing his law school papers at Harvard.

She eventually transferred to Columbia Law School where she graduated first in her class. The Ginsburg marriage is a case study in the power that exists in a relationship when both spouses see one another as equals. As Dahlia Lithwick points out in The Atlantic, “Yet this romance for the ages—which it certainly proved to be—was also a business partnership almost unrivaled in feminist history. They both went to law school, they both worked, they had a daughter and a son, and they tried their first big gender-equality lawsuit together.”

To a fascinating and profound extent, their marriage is a demonstration of the power of gender equality: when assumptions about gender within a marriage are not made, and both parents see themselves as the sometimes breadwinner, sometimes caretaker, but always a booster of the other, the potential for all members of the family, children included, is greater than the sum of its individual parts.

Young and ambitious Americans who see their lives in sad binary terms, of having to choose between professional ambitions and personal relationships, would do well to study the power of intertwined ambitions and unyielding marital commitment.

Politics Should Never Trump Friendship

On issues of controversial constitutional interpretation, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia could not have been more different. He was the archconservative who laced his opinions with unending vim and brazen pugnaciousness, she is the iconic and much-lionized liberal icon whose legal opinions, ironically, always read as more restrained.

And yet, the intense and wholly genuine friendship between the two of them is a powerful reminder of how Americans should approach their political differences. For those who doubt that there is a market for such a traditional view of political rivalry, consider that in the past decade there have been countless articles, news features, and even an operatic treatment of their usual friendship, “Scalia/Ginsburg: A (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions.”

This keen interest in their friendship is powered by a raw but inchoate sensation that they knew something we have forgotten. Their friendship was anchored as almost all-powerful friendships are—in common loves and interests. They celebrated New Year’s Eve Together, rode elephants together in India, spent a lifetime cultivating their love for American law and constitutional judgment, and of course, attended opera with one another.

Sadly, many modern Americans absolutely cannot fathom a compartmentalizing of the political and the personal. There are two approaches to dealing with the sad but intense division in America’s body politic today: when encountering the ideas, words, and actions of tens of millions of Americans you fundamentally disagree with, one can either conclude these people are motivated by the worst of intentions, that their aims are sinister and their ideals apocalyptic. You can use fancy terms like “Orwellian” or “Potemkin” to describe them.

The other, and preferable, approach is the one adopted by both Ginsburg and Scalia. They assume there is something they don’t quite understand in the other and they work hard—very hard—to overcome their ignorance. It doesn’t mean one changes the content or vitality of his/her convictions, but it humanizes ideas with which one is at variance.

But even more, it can strengthen or reaffirm one’s convictions.

As she recalled, “I disagreed with most of what he said, but he said it in such a charming, amusing way. And if truth be told, if I had my choice of dissenters when I was writing for the court, it would be Justice Scalia, because he was so smart, and he would hone in on all the soft spots, and then I could fix up my majority opinion.”

It is not a coincidence that two constitutional titans at opposite ends of the political and legal spectrum were able to cultivate a deep and enduring friendship. Judges are not able to get away with conducting their business with platitudes, clichés, and bumper stickers. They verbally joust, intellectually argue, and the only way to do this is to spend considerable time digging into the details of one’s thoughts and convictions. The deeper the digging, the more likely it is for others to find a common humanity, a unifying thread or root connecting trees in a national orchard that seem to be both separate and growing apart. In this sense, we should all emulate the disposition of judges.

The Scalia-Ginsburg relationship should offer us the following commandment: let’s get our shovels and go digging . . . with one another.