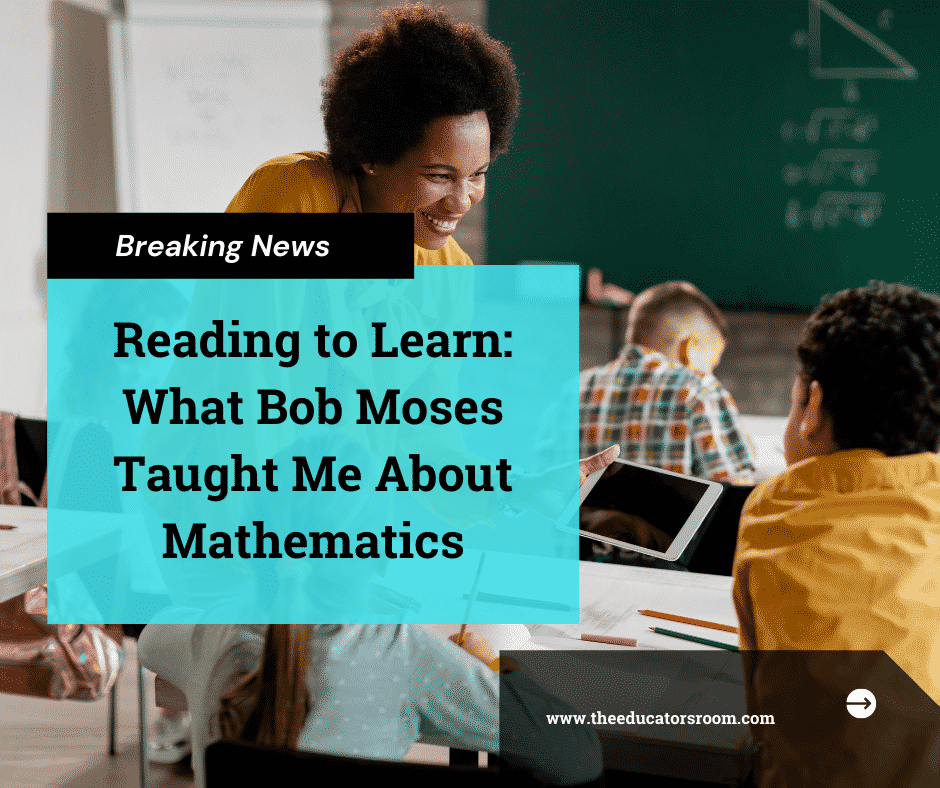

Kim Lee is a physics teacher at Pinole Valley High School in West Contra Costa Unified School District. She has been teaching for the last four years. She is the teacher sponsor of the Anti-Racism Club and helps run the Peer Tutoring Program. She is committed to promoting diversity and equity through STEM education, as well as creating an inclusive school climate and classroom.

Bob Moses, known for his leading role in the registration of Black voters in Mississippi directly in the face of extreme violence and intimidation during the Civil Rights Movement, died on July 25, 2021. Like the few who I’ve spoken to about Moses since his passing, I could only vaguely link his name to the Civil Rights Movement but had no knowledge of the details and significance of his actual work. This in itself is a prime example of the dire need to rethink how we teach history in American public schools, especially given the relevance of his work expanding voting access to Black people to the blatant assault on voting rights we witness today. Here I will focus not on the sad fact that I knew nothing about Moses until a few weeks ago, but on what I’ve learned about his work and philosophy since.

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, there has been a renewed understanding amongst some educators of the need to take a deep look at the inequities we witness firsthand in our classrooms and how they result from and continue to perpetuate the rippling effects of anti-Blackness, systemic racism, and implicit bias embedded throughout the American education system. As we, particularly those of us who are not Black and therefore have not lived the Black experience, work to expand our understanding of the problem, we can simultaneously acknowledge that we are often at a complete loss of how to contribute to the solution of said problem. That is because racism and racial inequity in education cannot be simplified into a single problem with a single solution.

In addition to the lifelong work of examining our own implicit biases, one of the more immediate things we can do comes straight from the philosophy that drove the lesser-known second half of Bob Moses’ life as a Civil rights activist and leader.

This latter half began in 1982 with the founding of the Algebra Project, a math literacy program that targets low-income students and students of color. We can all rethink how we view and prioritize the importance of math and science literacy, regardless of what subject we teach or the field we specialize in. Specifically, we can begin to view fluency (measured not just by a class grade) in Algebra as one of a few primary gatekeepers to college preparatory courses. In this day and age, it is a key that is just as vital to equal citizenship as voting (as Moses wrote about in his book Radical Equations). Many still view Algebra as primarily an A-G, college-ready, box that students have to check, but the disproportionate levels of Algebra fluency that exist must be addressed with due diligence before we can ever truly achieve diversity, inclusion, and sense of belonging in college preparatory classes across all racial and socioeconomic groups. Fortunately, Moses’ Algebra Project already exists as a model for the philosophy that we should widely adopt and the work we must do.

Many educators are familiar with the concept of “learning to read, then reading to learn.” The concept states that students spend their earlier years (kindergarten through third grade) learning the basics of reading, like phonics and decoding, before they reach a transition point in the fourth grade where they then apply those reading principles to take in information. I will use this concept as an analogy simply to illustrate that Algebra, at its core, is not just a branch of math but a language.

Using symbols instead of words is a simple yet powerful language that we can use to describe and understand complex relationships and systems that exist in the real world. After acquiring fluency in the basics of Algebra, students are ready to apply those principles to grasp college preparatory level math and science information. In an interview with the Washington Post, Moses said “The poorest kids, Black or White, can be taught to turn ordinary language into symbols that they can use to solve complex problems… [and] have the means of becoming involved in the nation’s knowledge economy and not get left behind.” If the fourth grade is the magical transition point for reading to learn, then the magical transition point for using Algebra to learn would come sometime in middle school in order to be prepared for high school math and science courses.

Leaving this analogy and reentering reality, we see many students (predominantly low-income students and students of color) leave middle school far below the levels of fluency in Algebra required to hit the ground running when they reach the high school level. The same can be said for some of those fundamental reading skills we expected by the fourth grade. I should clarify that singling out low-income students and students of color is not to fall into the trap of deficit thinking, but rather to highlight the result of years of schooling within a system we know to be based on a disturbingly uneven distribution of resources.

To address this, we can look back at our “read to learn” analogy, but this time at the modern critiques of the concept. Years of research have shown that “learning to read” and “reading to learn” should happen simultaneously and continuously throughout a child’s education, that each can and do supplement the other in the years before and in the years after the third grade. The same can be said about Algebra – students can and should learn the language of Algebra through the real-world experiences it is used to describe, while simultaneously enhancing their understanding of those real world experiences through symbolic representation throughout their high school experience.

Through his Algebra Project, Bob Moses developed a Five-Step Approach to teaching Algebra to diverse students that centered on student experiences. In fact, the first step comes straight from student experience, with the observing of a physical event. The five steps walk students through describing experiences using familiar forms of communication (pictures, talking) before eventually describing those same experiences using math symbols. In essence, students are taught to be able to describe their experiences using mathematical statements. According to Moses, using the description of physical experiences proved to be a starting point that was more accessible to students of all backgrounds, regardless of socioeconomic status, ethnic background, or home language.

It also answered the question often asked by skeptical Algebra students, “When will I ever use this?” by showing its relevance from the beginning. For thousands of poor (and often failing) students of color, some of who worked directly with Moses, the Algebra Project helped increase math literacy, success in ensuing math and science courses, and appreciation of Algebra’s importance as a tool for equal access to quality education.

All of this is to say that we should not believe the false notion that Algebra is simply a branch of math that is out of reach for many of our students. We cannot accept Algebra to be the class where countless students decide they are just not cut out for math or science. If we see Algebra fluency as one of the keys to economic access and mobility in the 21st century as Moses asserted, we cannot accept the current levels of fluency we see in many of our students, especially given the discrepancies of these levels across racial and socioeconomic groups. To begin addressing this requires a change in perspective, a willingness to see Algebra fluency as being as essential as the ability to read, and thus allocate some of our incredibly limited resources (while advocating for much, much more) to specifically target alarmingly low Algebra fluency levels amongst our most underrepresented student groups with priority.

Bob Moses’ death serves as a reminder that pursuing racial equity should be viewed as essential in math and science teaching, and that math and science teaching should be viewed as essential in pursuing racial equity. Moses himself spoke about the relative lack of support (or at least action based on support) for this idea despite the success of the Algebra Project’s initiatives over almost four decades in providing poor students of color higher levels of educational opportunity and economic mobility. As we grapple with what we can do to be part of the solution, we should remind ourselves that not all the wheels of activism need to be reinvented. There is no better way to honor the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement who didn’t make it into our history textbooks than to educate ourselves on, learn from, and continue the work they already began.