Have you signed up for The Educator’s Room Daily Newsletter? Click here and support independent journalism!

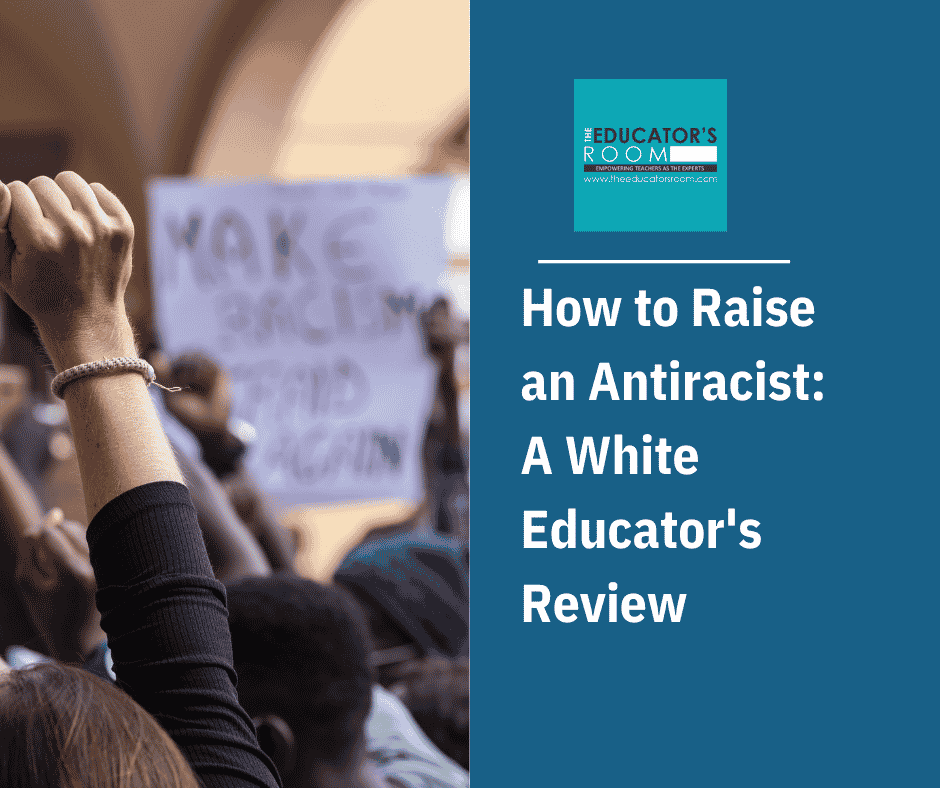

It’s safe to say scholar, professor, and author Ibram X. Kendi brought the term antiracist into our collective consciousness with his bestseller, How to be an Antiracist.

In his latest book, How to Raise an Antiracist, Kendi adapts his work for parents, teachers, and caregivers. For the first eighteen years of life, caregivers have endless opportunities to model intellectual honesty, develop critical thinking, and protect all children from the scourge of racism. For educators committed to antiracism, this book offers many takeaways.

The Intersection of Personal and Systemic

Kendi’s writing seamlessly shifts between personal experiences and the history of systemic racism that has created today’s society. As he says, “the most critical part of raising an antiracist child is not what we do with our child. It’s what we do with our society.”

Ibram divides the book’s chapters into stages of his daughter’s life through kindergarten. He then shifts to his memories of elementary, middle, and high school.

He writes candidly and vulnerably about his wife’s difficult pregnancy, missed opportunities to impart “antiracist antibodies” to his daughter, and his experiences as a Black boy and later man in America.

For example, when his daughter first coos, he explains that he fell into the American parenting trap of believing his own child had superior abilities. Of course, he knew children inherit both deprivations and privileges from their parents. But, because our society denies the existence of racist policies, he was duped into seeing his daughter’s “natural talent” instead of her “unnatural privileges.”

These moments of admitted missteps, from an antiracist scholar no less, are refreshing. All caregivers, no matter how educated or well-meaning, make mistakes because we live in a society founded on white supremacy.

Raising & Teaching Critical Thinkers

Children are naturally curious and intellectually honest because they “don’t have an ideological filter catching anything that challenges their worldview.”

Kendi explains that leaning into a child’s instinctual urge to question nurtures not only their curiosity but their empathy and antiracism as well.

Every caregiver has been asked “why?” sometimes in an endless stream. I appreciated how he highlights those questions as some of the most important learning opportunities we can facilitate. My favorite students are often the ones who ask questions, even the difficult, unanswerable ones because they are proof of their engagement and learning.

“We raise a critical thinker in much the same way we raise an antiracist,” Kendi explains. “Asking, not telling. Modeling, not lecturing. Radically changing the environment and ourselves.”

He uses scenarios we can all relate to from our own experiences to model challenging the status quo of our society. For example, he encourages us to ask, “Why do you think that man is homeless?” when passing a Latinx homeless man on the sidewalk. Questioning invites a conversation about equity, systems, and humanity. Diverting eyes or walking faster, as many parents might do on instinct, does the opposite. These actions nonverbally teach a child that a homeless person is someone to be looked down upon, feared, or ignored.

It’s an antiracist caregiver move to help students challenge what they see around them and find answers.

The Power in HOW We Teach

One of the most striking questions Kendi asks in this book is, “who is going to protect White babies from White racism?”

This question hit home as a White teacher in a predominantly White public high school.

Caregivers of color are more likely than White parents to protect their children from White racism, as it obviously impacts most aspects of their lives. On the other hand, White parents generally practice colorblind racial socialization. Most White parents avoid mentioning race with their children, even though it impacts their lives too.

Similarly, a lot of educational scholarship focuses on uplifting our students of color, as it should, but pays less attention to the impact of inadequate teaching and homogeneous schools on White children.

Teachers know their students are watching them. Students pay close attention even and especially in everyday moments that may seem mundane or routine.

So, if a White teacher disproportionately disciplines a Black student in their classroom, this targeting has a “teaching effect.” Not only does it harm the student who is targeted. It also nurtures “the racist perceptions of children who witness this disparate treatment.” The White students in the room have yet another example to add to their “anti-Black bias,” which develops in most White children by age six.

If we don’t teach differently, the cycles of racist thought perpetuate.

The Power in WHAT We Teach

We know that the school curriculum has been whitewashed, but Kendi focuses not only on the harmful effect this has on children of color but on White children as well. While children of color are erased from the curriculum, White children do not learn the truth of their racial history.

Whenever I do identity work in my class, many of my White students struggle to identify what their culture, heritage, or traditions even are. Of course, they’re a part of the dominant narrative, which seems so “normal” as to not even be identifiable, but they still feel a void there.

“What students are not learning–the absences in their education–can be more harmful than what they are learning,” Kendi writes. “Educators teach what they don’t teach.”

Kendi couldn’t publish a book about race and education in 2022 without touching on Critical Race Theory. In the afterword, he delves into the primal fear that White people will be painted as villains.

But, the irony for those labeling CRT as indoctrination is that if we don’t teach the truth, we leave out the complex truths of all races. For example, to fully teach the history of slavery, teachers can share about White abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, as well as slaveholders. There’s never one narrative. The fear many people have about teaching true history makes it glaringly obvious what they’ve never learned.

Without opportunities to question, discuss, learn, and find inherent worth in their humanity, students will be “vulnerable to their own ignorance.” Ignorance is the antithesis of the purpose of our schools.

Worth the Read

If you’ve read How to Be an Antiracist, this is an excellent companion. If you haven’t, pick that one up first because he dives far deeper into the systemic inequities that make raising an antiracist imperative.

With an empathetic heart and tightly researched writing, How to Raise an Antiracist asks all caregivers to model their own critical thinking in the best interest of their young people.

Kendi ends the book on a hopeful note (his daughter’s name, Imani, means faith in Swahili) and invites readers to truly imagine an antiracist society.

He admits, “Like so many of us today, I had to learn as an adult what I could have learned as a child,” but we have an opportunity to change that. Because “young people are ready to be antiracist,” as teachers who truly create the space for intellectual curiosity know.

“The more our children know, the stronger their foundation to question injustice and unfairness, and to protect their own minds from propagandist lies.”

The more we know, the more we can help our young people grapple with their reality. How to Raise an Antiracist is an excellent primer for any adult who cares about the children in their lives.

Editor’s Note: If you enjoyed this article, please become a Patreon supporter by clicking here.