My niece is a beautiful little girl. She is a beautiful girl on the outside, the kind of little girl who cannot take a bad picture. She is also beautiful on the inside. She is her mother’s helper, fiercely loyal to her older brothers, and a wonderful example for her younger brother and sisters. She is the gracious hostess who makes sure you get the nicest decorated cupcake at the birthday party. She has an infectious laugh, a compassionate heart, and an amazing ability “to accessorize” her outfits. For the sake of her privacy, let’s call her Madelyn.

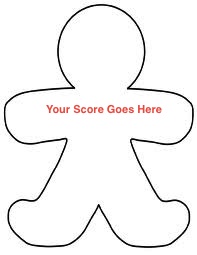

Two years ago, the teachers at her school, like teachers in thousands of elementary schools across the United States, prepared Madelyn and her siblings for the mandated state tests. There were regular notices sent home throughout the school year that discussed the importance of these tests. There was a “pep-test-rally” a week before the test where students made paper dolls which they decorated with their names. A great deal of time was spent getting students enthused about taking the tests.

Several months later, Madelyn received her score on her 4th grade state test. She was handed her paper doll cut-out with her score laminated in big numbers across the paper doll she had made.

Several months later, Madelyn received her score on her 4th grade state test. She was handed her paper doll cut-out with her score laminated in big numbers across the paper doll she had made.

Madelyn was devastated.

She hated her score because she understood that her score was too low. She hid the paper doll throughout the day, and when she came home, she cried. She could not hang the paper doll on the refrigerator where her brother’s and sister’s scores hung. The scores on their paper dolls were higher.

She cried to her mother, and her mother also cried. Her mother remembered that same hurt when she had not done well on tests in school either. As they sobbed together, Madelyn told her mother, “I’m not smart.”

Now, the annual testing season is starting again. This year, there will be other students like Madelyn who will experience the hype of preparation, who will undergo weeks of struggling with tests, and then endure a form of humiliation when the results return. The administrators and teachers pressured to increase proficiency results on a state test, often forget the damage done to the students who do not achieve a high standard.

That paper doll created during the fervor of test preparation is an example of an unintended consequence; no one in charge considered how easily scores could be compared once they were available to students in so public a manner. Likewise, many stakeholders are unaware that the rallies, ice-cream parties, and award ceremonies do little to comfort those students who, for one reason or another, do not test well.

There is little consolation to offer 10-year-old students who see the results of state tests as the determiner of being “smart” because 10-year-old students believe tests are a final authority. 10-year-old students do not grasp the principles of test design that award total success to a few at the high end, and assign failure to a few at the low end, a design best represented by the bell curve, “the graphic representation showing the relative performance of individuals as measured against each other.” 10-year-old students do not understand that their 4th grade test score is not an indicator of later success.

Despite all the advances in computer adaptive testing using algorithms of one sort or another, today’s standardized tests are limited to evaluating a specific skill set; true performance based tests have not yet been developed because they are too costly and too difficult to standardized.

My niece Madelyn would excel in a true performance based task at any grade level, especially if the task involved her talents of collaboration, cooperation, and presentation. She would be recognized for the skill sets that are highly prized in today’s society: her work ethic, her creativity, her ability to communicate effectively, and her sense of empathy for others. If there were assessments and tests that addressed these particular talents, her paper doll would not bear the Scarlet Letter-like branding of a number she was ashamed to show to those who love her.

Furthermore, there are students who, unlike my niece Madelyn, do not have support from home. How these students cope with a disappointing score on a standardized test without support is unimaginable. Madelyn is fortunate to have a mother and father along with a network of people who see her all her qualities in total; she is prized more than test grades.

At the conclusion of that difficult school year, in a moment of unexpected honesty, Madelyn’s teacher pulled my sister aside.

“I wanted to speak to you, because I didn’t want you to be upset about the test scores,” he admitted to her. He continued, “I want you to know that if I could choose a students to be in my classes, I would take Madelyn…I would take a thousand Madelyns.”

It’s testing season again for a thousand Madelyns.

Each one should not be defined by a test score.