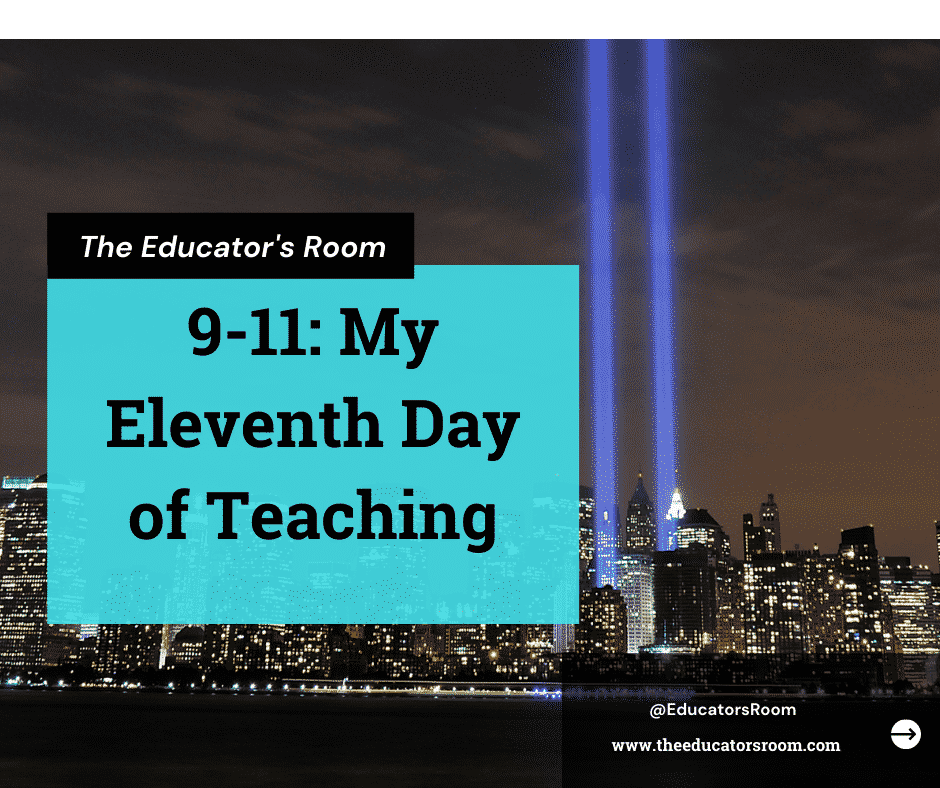

On Sept. 11, 2001, it was my eleventh day of teaching. As I headed into my seventh-grade language arts classroom at 7:30 a.m., I was already sweating in the lingering summer heat of early September. A few posters on the mostly bare wall hung haphazardly in the humidity, mirroring my own wilted exhaustion. I was a fresh college graduate and newlywed, drowning in papers to grade, behaviors to manage, curriculum to plan, and wading through the hormone hurricane unleashing itself on my classroom daily. By 8:00, my students were straggling in, a few muttering “Good morning” and “Hey, Mrs. Khon.” The first hour was always the quietest, the sleepiness not yet having made an about-face into hyperactivity. We dove into the morning warmup and our current reading piece, and soon the bell rang for the second period.

I made a quick dash to the office to use the restroom. Donna, our secretary, was standing at her desk, which didn’t seem all that unusual at first until I noticed she wasn’t moving. She seemed frozen, a statue carved in front of her computer screen. “What’s up?” I casually asked, coming back around the counter. She didn’t answer immediately, and I then saw another secretary standing behind her.

“A plane hit the World Trade Center, “ she replied.

“Where’s that?” I asked.

“It’s a skyscraper in New York City.”

“Like it was an accident, or what?” I asked.

“They don’t know.”

“Oh, man. That’s awful,” I replied. I headed back down the hallway to my room as the warning bell rang, my mind already on the next period.

I wandered back into the office 50 minutes later between my third and fourth hour, and this time, our principal, the counselor, both office assistants, and a handful of other teachers were milling around.

Glancing my way, Dona told me, “Another plane hit the tower.”

“Geez, I guess it wasn’t an accident!” I exclaimed. “What happened?”

“They don’t know yet,” she murmured.

I once again scanned my mailbox and found a printed copy of the latest news release regarding the incident. But, unfortunately, it had a blurry black-and-white photo of a tall tower with a gaping, smoking hole in the side.

Mobile devices (and the instant information they provided) didn’t exist yet the way they do now- students and most adults didn’t even own one. Yet by lunchtime, parents were calling; a handful pulled their kids out of school for the day. By my prep hour in the sixth period, the news was constantly on, replaying the collapse of the towers, the screams of shocked New Yorkers, and the horrified silence of the news anchors magnifying the devastation. My coworkers and I flitted back and forth across the hallway with “Did you see…” and “Have you heard…?” Driving the 30 minutes to my apartment after school was dismissed, my eyes barely saw the road as my ears absorbed unfathomable details. My husband met me at home, and his coaching duties and all other school events were canceled in light of any unforeseen threats. For hours, we sat glued to the television, watching bodies fall from windows, pedestrians run from clouds of ash, and the desperate pleas of families searching for loved ones. The Pentagon. Flight 93. It was exceptionally disturbing, yet we could not look away as the hours bled into midnight and beyond.

And then I had to go back to school.

I wasn’t trained in what to say or do: I was a newbie with zero formal education or practical experience in social-emotional learning, counseling, PTSD, or trauma. I didn’t even know then what those terms meant. But I did know that my students would have heard and seen the news, and they were scared, confused, curious, and more. They were living through a historical event of unprecedented tragedy and magnitude, and grammar or reading logs weren’t the most important topics to cover anymore. Their emotions were frayed and on edge. They couldn’t really focus on anything else and didn’t know what to do with what they were feeling, and frankly, neither did I.

So I just let them talk for days. I listened to them tell me how awful it was to think about choosing to burn alive or fall to your death. They told me the eerie sound of the firefighters’ chirping Personal Alert Safety Systems haunted them – like the sound of hundreds of ghosts. They asked questions I couldn’t answer: Who would do that? Why did they do that? Are all the people on the planes dead? I told them it was okay to cry, and some did. They told me it was okay to cry when I found out Meredith Whalen, my high school track teammate and church acquaintance, died on the 93rd floor of 1 World Trade Center. She was 23 years old.

And then I let them write. I told them this would be something they would never forget. “Where were you on 9-11?” would be a question they’d always have an answer for. They poured out their emotions: horror, anger, disgust, sadness, morbid fascination – all of it came to roost in the pages of their journals, and for the first time, they realized writing actually WAS recording history. The American Flag became a necessary decorative item and fashion piece. They watched a nation forge a stern resolve to avenge this terrorist act. Eventually, they too saw their country enter a war in foreign lands. We returned to reference this throughout the months to come. As we read The Giver, The Diary of Anne Frank, Zlata’s Diary, and Daniel’s Story, we came to recognize them as more than just books; they were teenage experiences written from the pain of history. Those students are approximately 32 years old now, yet I’d wager they remember that day with some clarity, muddled as it may seem by time.

A few years back, I took a trip with some friends to New York City. I visited the Statue of Liberty, took a run in Central Park, ate at Tavern on the Green, took a Taxi to see “Wicked” on Broadway, had pasta in Little Italy, and walked Times Square at 2 a.m…but the one thing I couldn’t bring myself to do? Visit Ground Zero and the Freedom Tower. Standing in the shadow of the massive skyscrapers and realizing just how HIGH they were, visiting a high-rise hotel and envisioning a PLANE crashing into the windows, walking in the very streets, many fled down; it all felt even more unbelievably terrifying. I couldn’t bear to see the crushed fire trucks, the charred remains of the towers, and Meredith’s name engraved on a wall. It seems uncourageous of me in retrospect, but I knew the emotional toll it would take to relive those horrible moments.

This fall begins my 21st year of teaching and the 20th anniversary of 9-11. As an elementary school librarian now, I read to my students about what 9-11 was, as they weren’t even born yet, and most of their parents were young adults or teenagers. Our conversation has to be censored for their age and maturity level. Much of it is too scary and violent. We stick to basic facts; they have no frame of reference or developmental experience to process such information. But they can look it up on the internet, read about it in books, and hear their family’s stories. They still always have lots of questions: What happened? Why would someone do that? How many people died? Were you there? The rabbit trail conversations that inevitably follow usually command most of my time with them for the week. They still seek the same answers and reassurance my students did 20 years ago. I find talking about it deeply saddening and upsetting, rather like ripping a mostly-healed wound open again. I often cry in front of my students, my tears quicker to flow than they did years ago in front of snarky teenagers. The rawness of that day has faded over the decades, yet somehow it becomes fresh again each year. But my students need to know, and we shouldn’t shy away from remembering and honoring just because it’s painful.

This September, I will, for the twentieth time, walk my students through 9-11.

Then, they will come into the library, have a seat, and I’ll begin: “On September 11, 2001, it was my eleventh day of teaching…

Meran Khon holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Spring Arbor University and a Master of Education in Middle-Level Education degree from Walden University. She taught seventh-grade language arts and a third-grade self-contained classroom before reinventing the library and computer lab into a twenty-first-century Learning Lab/Maker Space, where she currently teaches K-5 students.